The longbow was a crucial English weapon of war and King Edward III’s second Archery law of 1363 made it obligatory for Englishmen to practise their archery skills every Sunday. Stray arrows proved to be extremely dangerous and the wind played a part in diverting arrows away from their intended targets. The answer they came up with was the weather vane, the word vane coming from the Old English word fana meaning flag. They were originally fabric pennants and lots of high buildings were fitted with them, not just churches. Compass points were added later.

The vanes developed into the more permanent metal structures we still see today, and I used one of the recent lovely sunny days to venture into the City and photograph a selection of them.

My first stop was the beautifully restored St Lawrence Jewry which took its name from a Jewish community that lived nearby during the early medieval period (EC2V 5AA). The Jews came to London at the time of the Norman Conquest and were expelled from England by Edward I in 1290. In the medieval period there were several churches dedicated to St Lawrence in London, and this one was named St Lawrence Jewry to distinguish it from other churches dedicated to the same saint. The nearby street called Old Jewry recalls the medieval Jewish presence here.

St Lawrence was martyred in San Lorenzo on 10 August 258 AD in a particularly gruesome fashion, being roasted to death on a gridiron. At one point, the legend tells us, he remarked ‘you can turn me over now, this side is done’. Appropriately, he is the patron saint of cooks, chefs and comedians and the church weathervane consists of a gridiron …

If you were born within the sound of Bow Bells you were considered a true Cockney and the Wren church on Cheapside has a weathervane that consists of a copper dragon (symbol of the City) nearly nine feet long (EC2V 6AU). You can see the cross of St George under its wing (the cross was originally painted red but the weather has worn this away) …

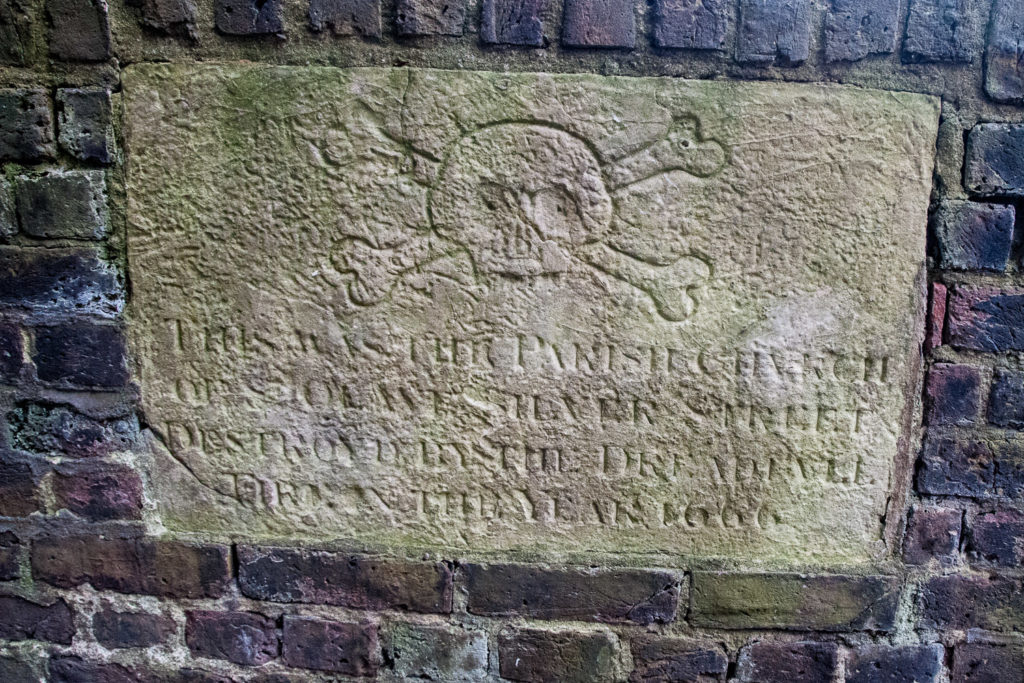

The dragon is very old and dates back to the rebuilding of St. Mary-le-Bow in 1679 after the Great Fire. Records show that a sum of £4 was paid to Edward Pearce, Mason, for carving the wooden model on which the dragon was based; and that a further £38 was paid to Robert Bird, the coppersmith who made the dragon itself. It is said that when the dragon was raised to its pinnacle it was accompanied by the famous Jacob Hall, a noted trapeze artist of the time, who performed a high wire act to the astonishment of the watching crowd.

When the dragon was repaired and restored after the Second World War it was lowered into place by helicopter!

There is a fascinating story about the consequences of allowing the dragon to meet the grasshopper from the Royal Exchange and you can read it, and much more, here in the splendid History London blog.

The Royal Exchange grasshopper may be even older, dating back to the original Exchange built in 1567. You can read a fascinating story about its restoration here.

The grasshopper is the symbol of Thomas Gresham, the founder of the original Royal Exchange. The story goes that one of Thomas’s ancestors, Roger de Gresham, was abandoned as an infant in the marshlands of Norfolk and would have perished had not a passing woman been attracted to the child by a chirruping grasshopper. Heraldic spoilsports assert that it is more likely a ‘canting heraldic crest’ playing on the sound ‘grassh’ and ‘gresh’.

I have written an entire blog about Gresham and you can view it here and my blog about the Royal Exchange can be accessed through this link.

The beaver above 64 Bishopsgate (EC2N 4AW) is a reminder of the Hudson’s Bay Company, which was founded by a Royal Charter in 1670 and had its headquarters nearby. The Charter granted a group of investors a monopoly on trade in the Hudson Bay region of North America, known as Rubert’s Land, and for centuries was dominant in the fur trade. Beaver fur was much sought after, particularly in the making of hats …

We are so lucky to still be able to admire the pre-Great Fire church of St Helen’s Bishopsgate (EC3A 6AT) …

And I just managed to get a picture of its pennant weathervane with the beaver in the background …

Pennants are common on weathervanes, flat metal equivalents of the original fabric versions. This one is on the tower of St Giles’ Cripplegate and dates from 1682 (EC2Y 8DA) …

It is difficult to imagine churches built by Sir Christopher Wren being demolished, but that was what was happening in the 19th century as congregations declined and City land could be sold for substantial sums. One of the victims was St Michael Queenhithe, but its charming elaborate weathervane found a home atop St Nicholas Cole Abbey on Queen Victoria Street (EC4V 4BJ). Very appropriate as St Nicholas (aka Santa Claus) is the patron saint of sailors …

This close-up picture, along with many others, appears in Hornak’s book After the Fire and more details are available here on the Spitalfield’s Life blog.

The old Billingsgate Market building dates from 1876 and was designed by Sir Horace Jones, an architect perhaps best known for creating Tower Bridge but who also designed Leadenhall and Smithfield markets. Business boomed until 1982, when the fish market moved to the Isle of Dogs.

The south side of the old market today.

I love the original weathervanes at each end…

The weathervane at the west end of the market.

Similar weathervanes adorn the new market buildings in Docklands but they are fibreglass copies.

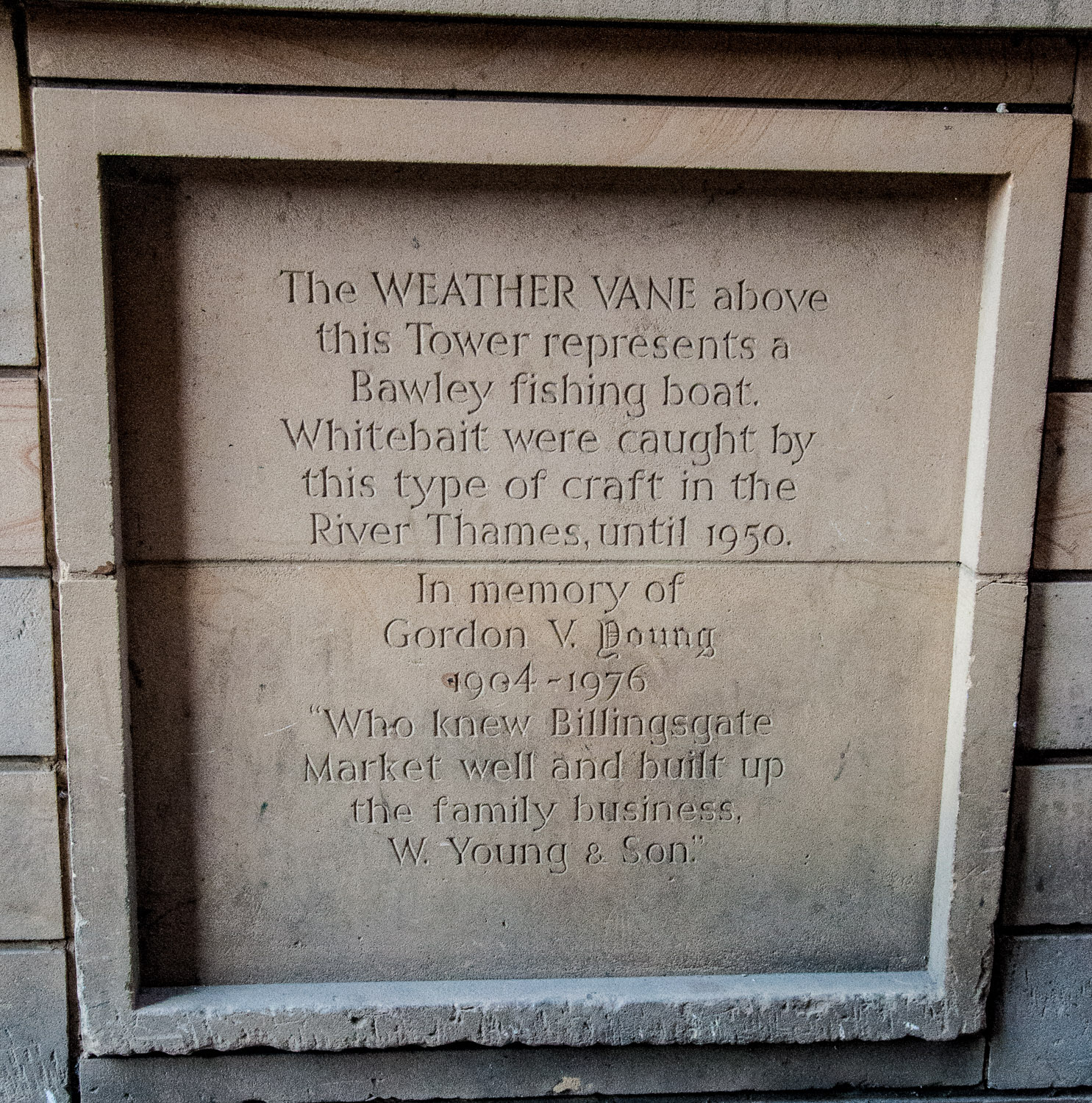

This Bawley fishing boat is situated across the road from the old market (EC3R 6DX) and commemorates Gordon V. Young, a well-known Billingsgate trader …

A plaque gives more information …

And finally, a weathercock.

The Church of St Katherine Cree in Leadenhall Street, one of the few to almost totally survive the Great Fire and the Blitz, has a rooster on its weathervane.

The St Katherine Cree weathercock with The Gherkin in the background

The Bible tells the story of St Peter denying Christ three times ‘before the cock crowed’. In the late 6th Century Pope Gregory I declared the rooster to be the emblem of St Peter and also of Christianity generally. Later, in the 9th Century, Pope Nicholas decreed that all churches should display it and, although the practice gradually faded away, the tradition of rooster weathervanes survived in many places.

If you can avoid colliding with someone intent on reading their smartphone, looking up as you walk through the City can be very rewarding.