Often when I look at war memorials I think about the life stories behind the names, some of which will obviously have been lost forever as memories fade and family members die. Sometimes, however, very detailed personal records have been accurately preserved for reasons other than just family history.

Such was the case for this vessel that departed Pier 54 in New York on 1st May 1915 bound for Liverpool. Her name is recorded here on the Mercantile Marine Memorial on Tower hill …

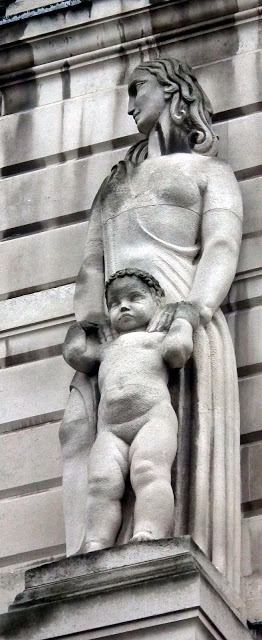

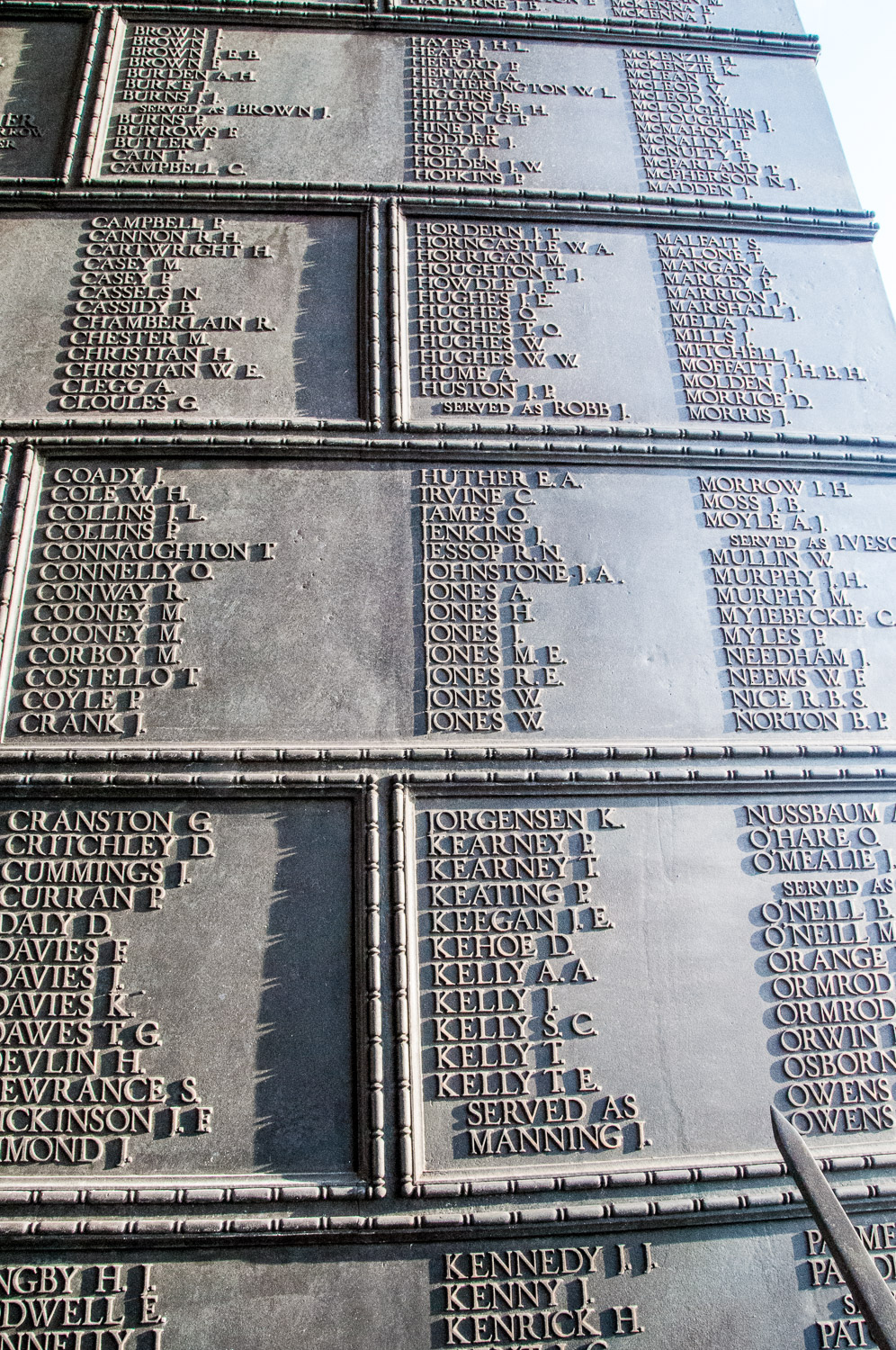

Below the name, as is the practice on the memorial, the names of the crew who were lost and whose bodies were never recovered are listed in alphabetical order …

Some of the tablets listing the Lusitania crew.

In total 1,193 people perished when the ship was sunk by a torpedo fired by the German U Boat U 20 on 7th May 1915 off the coast of Ireland. The number of crew lost was 402.

As I mentioned in an earlier blog, I was intrigued by men who chose to serve under names other than the name on their birth certificate and have researched many of them using the invaluable Merseyside Maritime Museum Lusitania database. One of the reasons this exists is that, since the crew were employees of the Cunard Line, insurance, pensions and the balance of their wages had to be distributed to their families, and so research was necessary to ensure the correct beneficiaries were identified.

On the tablet below are inscribed the names of three men in this ‘served as’ category – Kyle, Land and Pardew. Edward Kyle was 44 when he died and we don’t know why he chose to serve under the name of Robins. Similarly, we don’t know why Cann Cooper Land chose the name Jones when he signed up as a ‘Second Butcher’ on 12 April 1915 (although after his death the local paper stated ‘he was always known as Charlie Jones’). We do know he was 27 years old but gave his age as 25. In August 1915 his family was given the balance of his wages.

Much more is known about Charles Pardew who served as Charles John Scott …

Charles had been engaged as a fireman in the engineering department on a wage of six pounds ten shillings a month (£6.50). In July 1915 his widow Sarah swore an affidavit (supported by a lifelong friend called Fennell) that Charles had used the alias Scott since 1894. Apparently he had once sailed from Australia in a ship named the Charles Scott and decided to adopt that as his service name. For some reason he had also claimed he was 60 when in fact he was 57. Sarah received £300 compensation from the company and in August The Liverpool & London War Risks Insurance Association Limited granted her a monthly pension of one pound six shillings (£1.30).

There is someone on the memorial who shouldn’t be there at all …

We don’t know why Joseph Patrick Huston engaged as an able seaman under the name of Joseph Robb. His body was one of the first to be recovered, but for some reason the Commonwealth War Graves Commission was not aware of this, so his body was listed among the missing. He was 24 when he died and was buried in the Old Church Cemetery, Queenstown, County Cork on 10th May 1915.

The Lusitania mass burial ceremony. Joseph Huston’s body was among those recovered.

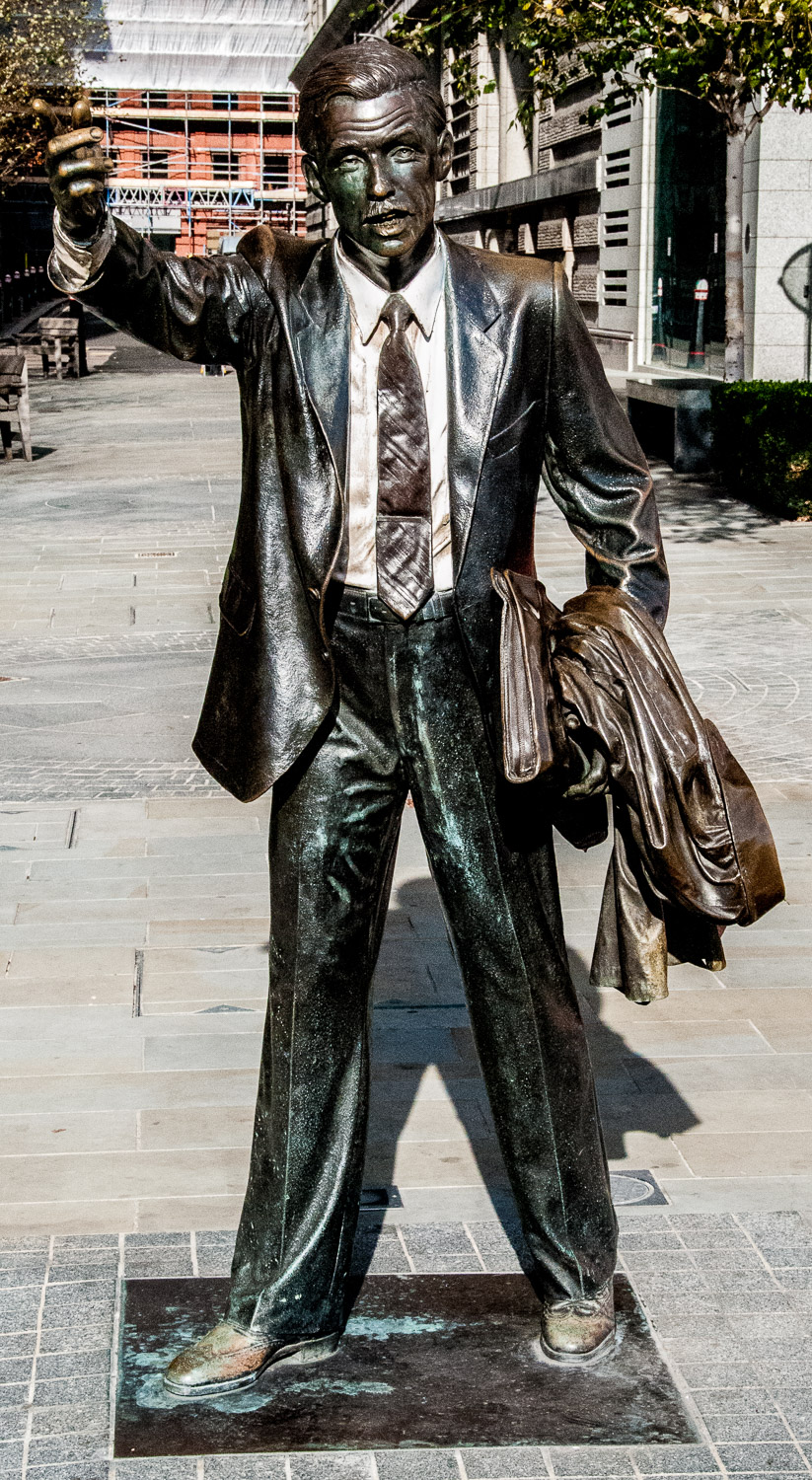

The memorial now …

I will carry on researching the Lusitania crew and will report back on any more interesting facts I come across.

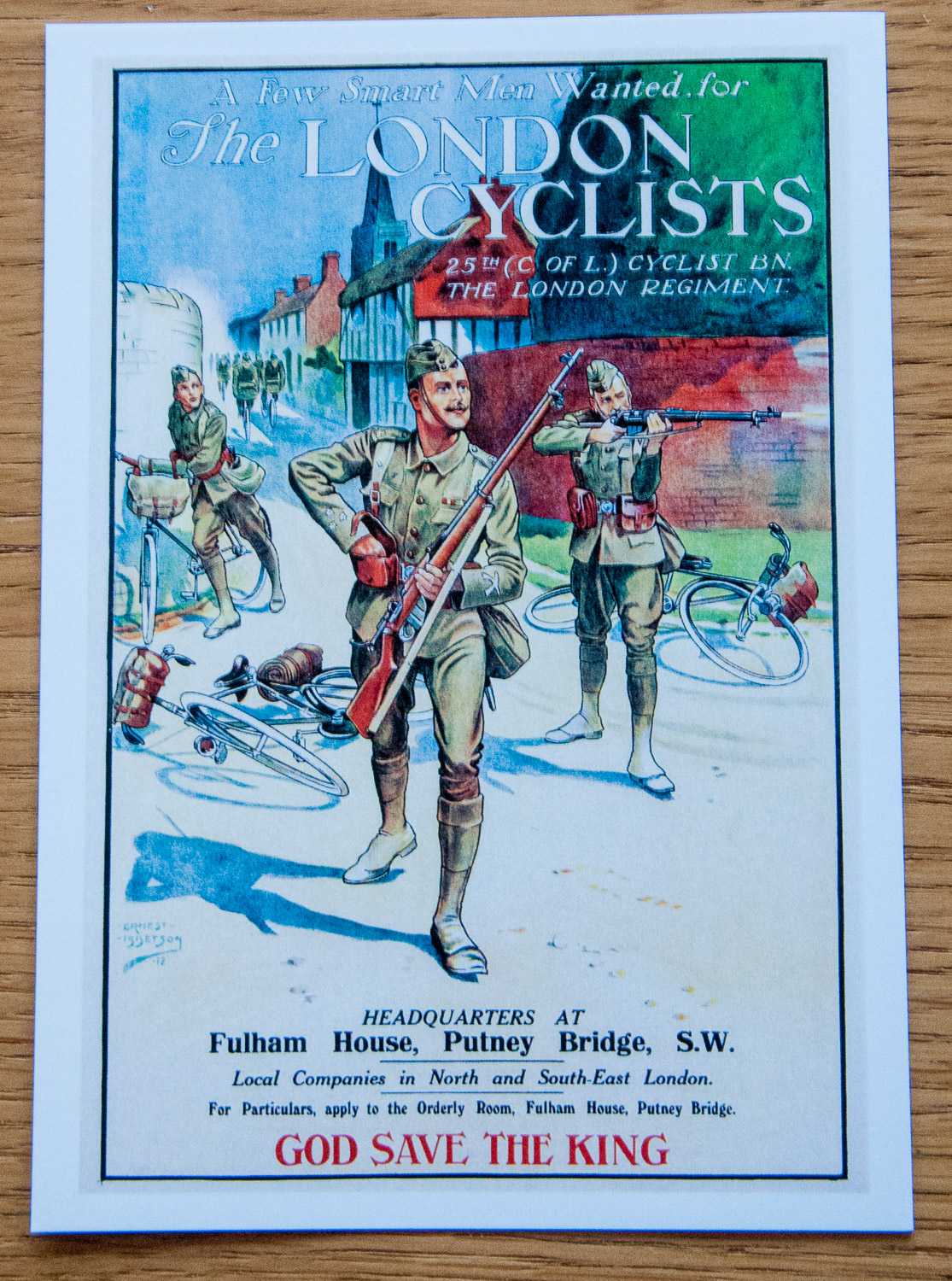

You may remember that in my blog of 25th October I mentioned the London Cyclists Battalion …

A recruitment poster from 1912.

It was therefore quite a coincidence that, on 9th November this year, Theresa May laid wreath at the grave of a cyclist, John Parr, the first UK soldier to be killed in the First World War on 21 August 1914. He was 15 when he signed up in 1912 but claimed to be eighteen years and one month. His comrades nicknamed him ‘Ole Parr’, which suggests that everyone knew he was much younger than he claimed, especially since on joining he was only 5 foot 3 inches tall and weighed just 8.5 stone!

John Henry Parr’s grave at St Symphorium Military Cemetery, Mons, Belgium.

Parr was a reconnaissance cyclist in the 4th Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment and died on the outskirts of Mons, Belgium. Bicycles were commonly used in the War, not only for troop transport, but also for carrying dispatches. Field telephones were also limited by the need for cables, and ‘wireless’ communications were still unreliable. So cyclists – and runners, motorbike riders, pigeons and dogs – were frequently preferred by both the Allies and the German army. There is an interesting article on the subject by Carlton Reid in Forbes magazine

I want to end this week’s blog with a story that moved me greatly when I reported it before in my blog about the City’s Little Museums.

These three battlefield crosses can be found in the crypt museum in All Hallows-by-the-Tower and I wrote in detail about the one in the centre …

This marked the grave of 2nd Lt. G.C.S Tennant. His last letter home was found unposted on his body after his death. It reads:

Sept. 2nd 1917.

Dearest Mother,

All well I come out tonight. By the time you get this you will know I am through all right. I got your wire last night, also your three letters. Many thanks for that little book of poems. It is a great joy having it out here. There is nothing much to do all day except sleep now and then. It will soon be English leave, and that will be splendid! I got hit in the face by a small piece of shrapnel this morning, but it was a spent piece, and did not even cut me. One becomes a great fatalist out here.

God bless you, your loving Cruff.

He was killed later that night, at about 4.00 am, and is now buried at Canada Farm Cemetery. He was 19 years old.

George Christopher Serocold Tennant (1897-1917).

After his death one of his men attested:

‘He was specially loved by us men because he wasn’t like some officers who go into their dug-outs and stay there, leaving the men outside. He had us all in all day long … The men would have done more for him than for many another officer because he was so friendly with them and he knew his job. He was a fine soldier, and they knew it.’

Incidentally, there is also a lovely tribute to the 83 men commemorated on the memorial outside Christ Church Spitalfields. It includes biographical details and a map of where they lived and surrounding areas. It was published in the Spitalfields Life blog and can be accessed here.