When I read that over 120,000 people had been interred in the Bunhill burial ground over the years it immediately made me think of Thomas Hardy’s 1882 poem The Levelled Churchyard

O passenger, pray list and catch

Our sighs and piteous groans,

Half stifled in this jumbled patch

Of wrenched memorial stones!

We late-lamented, resting here, are mixed to human jam,

And each to each exclaims in fear, ‘I know not which I am!’

About 2,500 monuments survive in Bunhill and it is possible to go on an accompanied walk through the stones, which are mostly now fenced off. In this short blog I am restricting myself to commenting on what can be seen from the public paths.

The history of the land is fascinating. Owned by the Dean & Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral between 1514 and 1867, it was continuously leased to the City Corporation who themselves sub-leased it to others. The name Bunhill seems to have been a corruption of the word Bonehill. Theories range from people being interred there during Saxon times to the suggestion that various types of refuse, including animal bones from Smithfield, were disposed of there. However, an extraordinary event in 1549 made the name literally true.

Since the 13th century corpses had been buried in St Paul’s churchyard just long enough for the flesh to rot away, after which the bones were placed in a nearby Charnel House ‘to await the resurrection of the dead’. After the Reformation this was seen as an unacceptable Popish practice, the Charnel House was demolished, and 1,000, yes 1,000, cartloads of bones were dumped at Bunhill. A City Golgotha, it is said the the resulting hill was high enough to accommodate three windmills.

In 1665 it was designated a possible ‘plague pit’ but there is no evidence that it was used as such. At the same time, however, a crisis arose concerning St Paul’s, the ‘noisome stench arising from the great number of dead’ buried there. Many other parishes had the same problem and the Mayor and Aldermen were forced to act quickly as a terrible smell of putrefaction was permeating the City. After negotiations with the existing tenants, the ‘new burial place in Bunhill Fields’ was created and had been walled in by the 19th October that year with gates being added in 1666.

The Act of Uniformity of 1663 had established the Church of England as the national church and at the same time established a distinct category of Christian believers who wished to remain outside the national church. These became known as the nonconformists or dissenters and Bunhill became for many of them the burial ground of choice due to its location outside the City boundary and its independence from any Established place of worship.

The last burial took place in January 1854 and the area was designated as a public park with some memorials being removed and some restored or relocated. Heavy bombing during the war resulted in major landscaping work and the northern part was cleared of memorials and laid out much as it is now with grassy areas and benches.

I have chosen a few memorials for you to look at as you walk through Bunhill from City Road in the East to Bunhill Row in the west.

I’d like to start just outside the east entrance on City Road and a few yards to the north. Look through the railings and you will see an obelisk memorial to this handsome gentleman. The inscription is in Welsh and marks the tomb of the Calvinistic Methodist minister, poet and Bible commentator James Hughes. Also inscribed is his Bardic name Iago Trichrug.

As you enter Bunhill you’ll notice that much of the path you are walking on consists of old grave stones, with some lettering still visible. I will point out a few along the way.

After passing through the east gate, look out on the left for this skull on the corner of one of the gravestones. Many of the stones are seriously eroded now but this one gives us an intimation of what the graves must have looked like originally.

This stone probably dates from the late 18th century judging by the others nearby

A little bit further on to the left is the memorial to Thomas Rosewell. The inscription reads

Thomas Rosewell

Nonconformist Minister

Rotherhithe

Died 1692

Tried for High Treason under the infamous Jeffries

See state trials 1681

The stone was renewed by a descendant in 1867

A Presbyterian minister in Rotherhithe, allegations (almost certainly fabricated) were made that he had uttered seditious sentiments during a sermon in September 1684. This led to his being arraigned for high treason at a trial presided over by the notoriously ruthless Lord Chief Justice, George Jeffreys, aka ‘The Hanging Judge’. He was initially found guilty and sentenced to death, but a tremendous public outcry led to a royal pardon in January 1685. Charles II had been told by an adviser that ‘If your majesty suffers this man to die, we are none of us safe in our houses’.

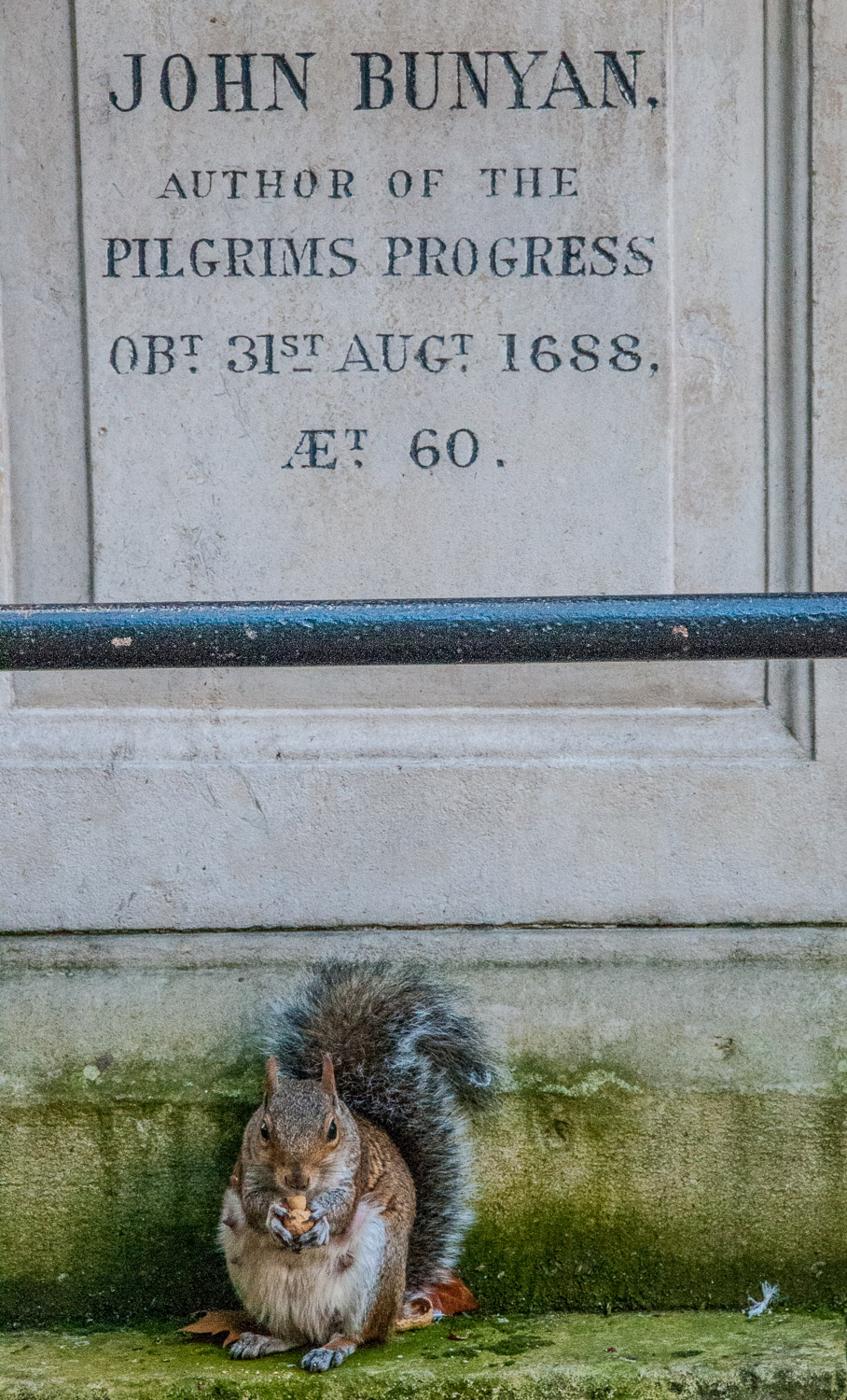

A little further on is John Bunyan’s tomb of 1689. It is not quite what it seems since the effigy of the great man and the bas-reliefs (inspired by Pilgrim’s Progress) were only added in 1862 when the tomb was restored. A preacher who spent over a decade in jail for his beliefs, he holds the bible in his left hand. He started the Christian allegory Pilgrim’s Progress whilst imprisoned and it became one of the most published works in the English language.

The Christian weighed down by his heavy burden of sin

Standing upright, free of sin, and clinging to the cross

Bunhill is a nice place for a quiet spot of lunch …

I was photobombed by a squirrel!

Old stones used as paving beside Bunyan’s memorial.

Turn your back on Bunyan’s tomb and you will be facing the obelisk erected in 1870 to commemorate the 1731 burial of Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe. The monument was funded by an appeal to boys and girls by the weekly newspaper Christian World who were invited to give ‘not less than sixpence’. Defoe got into serious trouble in 1702 by publishing a satirical work entitled The Shortest Way with Dissenters which was taken seriously by some and resulted in him being prosecuted for seditious libel. He spent time in jail and was also sentenced to three sessions in the pillory – supporters threw flowers instead of stones and garbage and he emerged unscathed to write a pamphlet entitled Hymn to the Pillory.

Defoe’s memorial

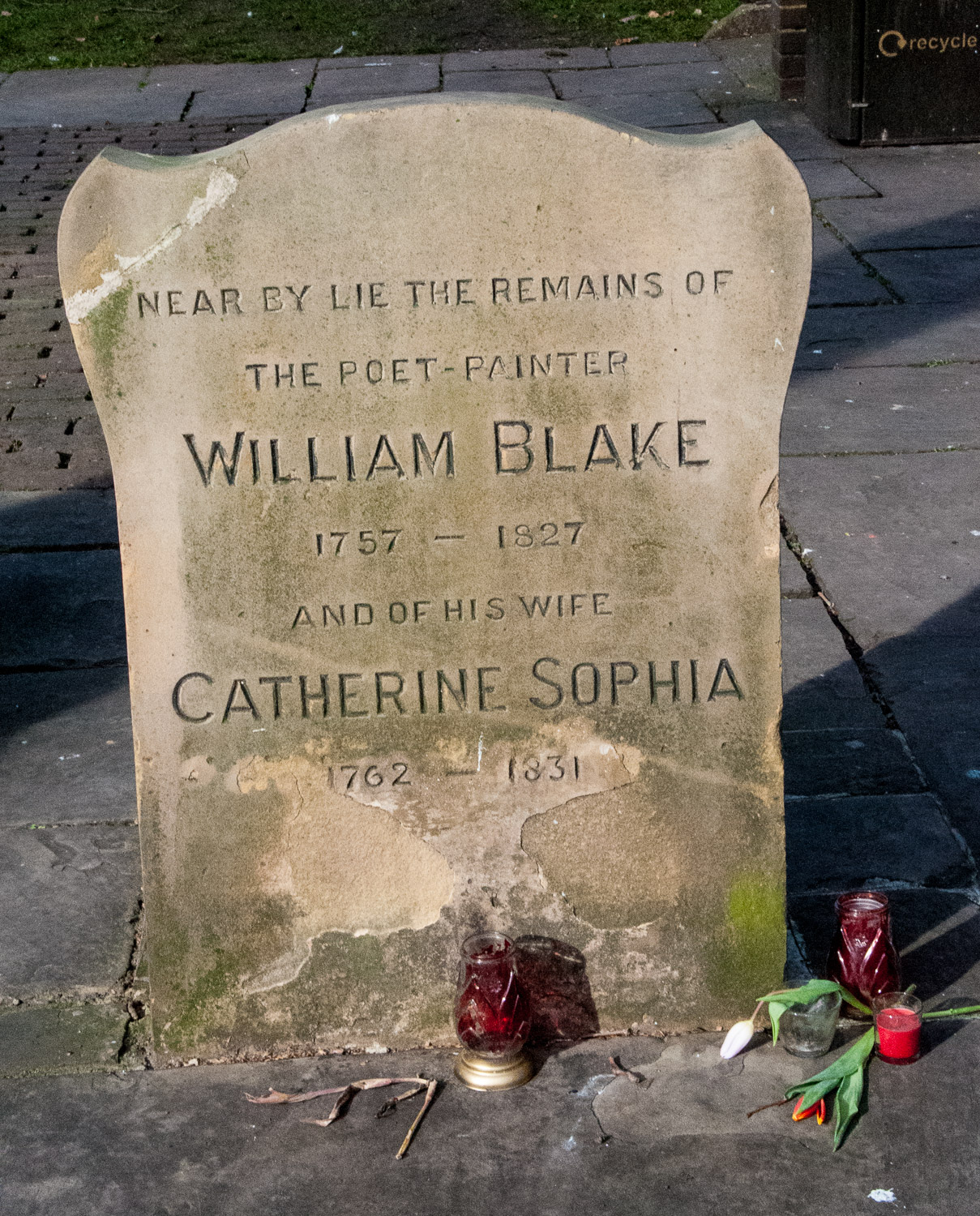

Paving nearby

Next to Defoe’s obelisk is the stone pictured below commemorating William Blake and his wife. The memorial was originally placed over his actual grave by The Blake Society on the centenary of Blake’s death (1927) but it was moved in 1965 when the area was cleared to create a more public open space. Candles, flowers and other offerings are frequently left here by modern day Blake admirers. Considered mad by many of his contemporaries, he is now regarded as one of Britain’s greatest artists and poets, his most famous work probably being the short poem And did those feet in ancient time. It is now best known as the anthem Jerusalem and includes the words that are often cited when people refer to the Industrial Revolution.

And did the Countenance Divine,

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these dark Satanic Mills?

Blake’s memorial with some offerings from modern day Blake pilgrims

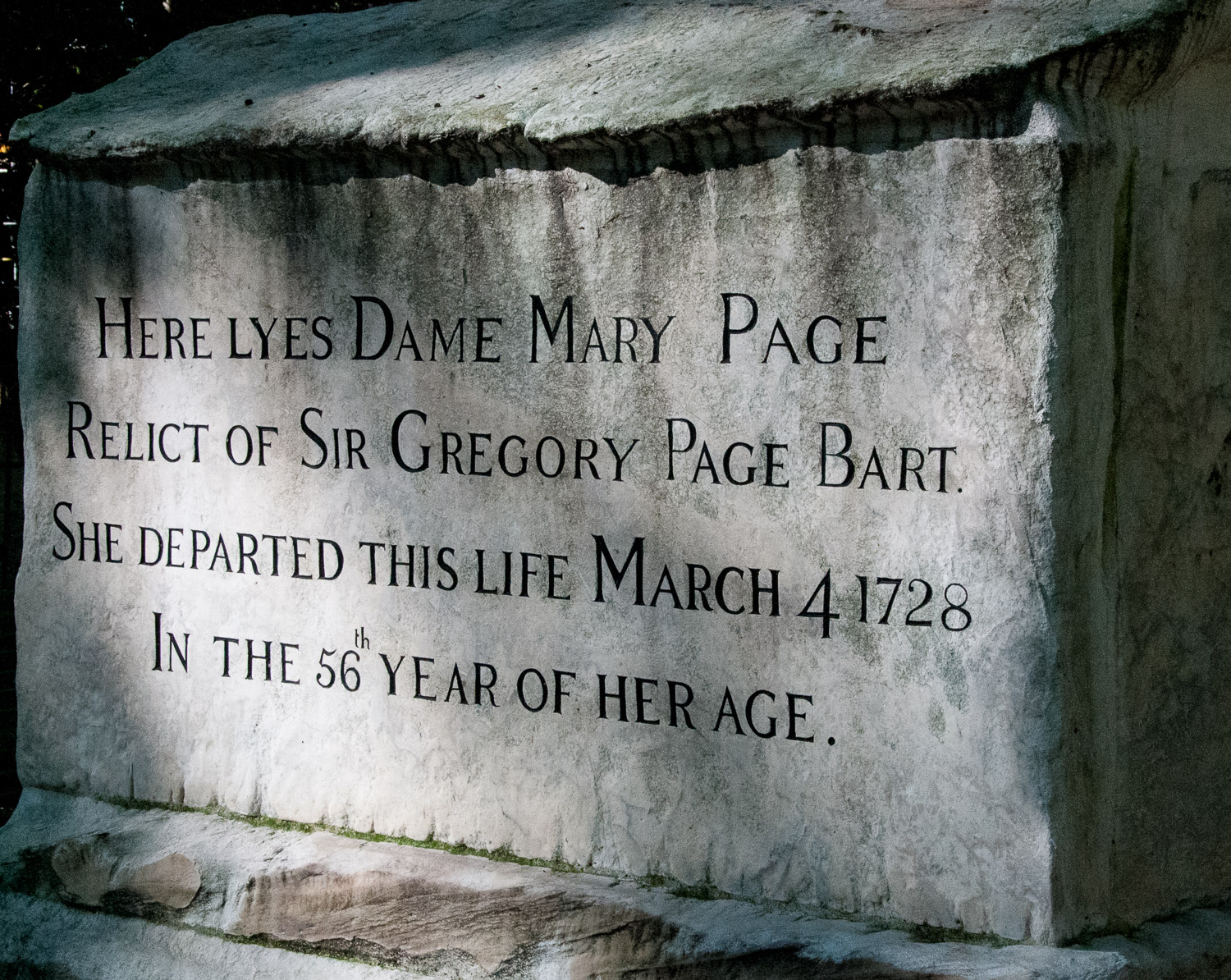

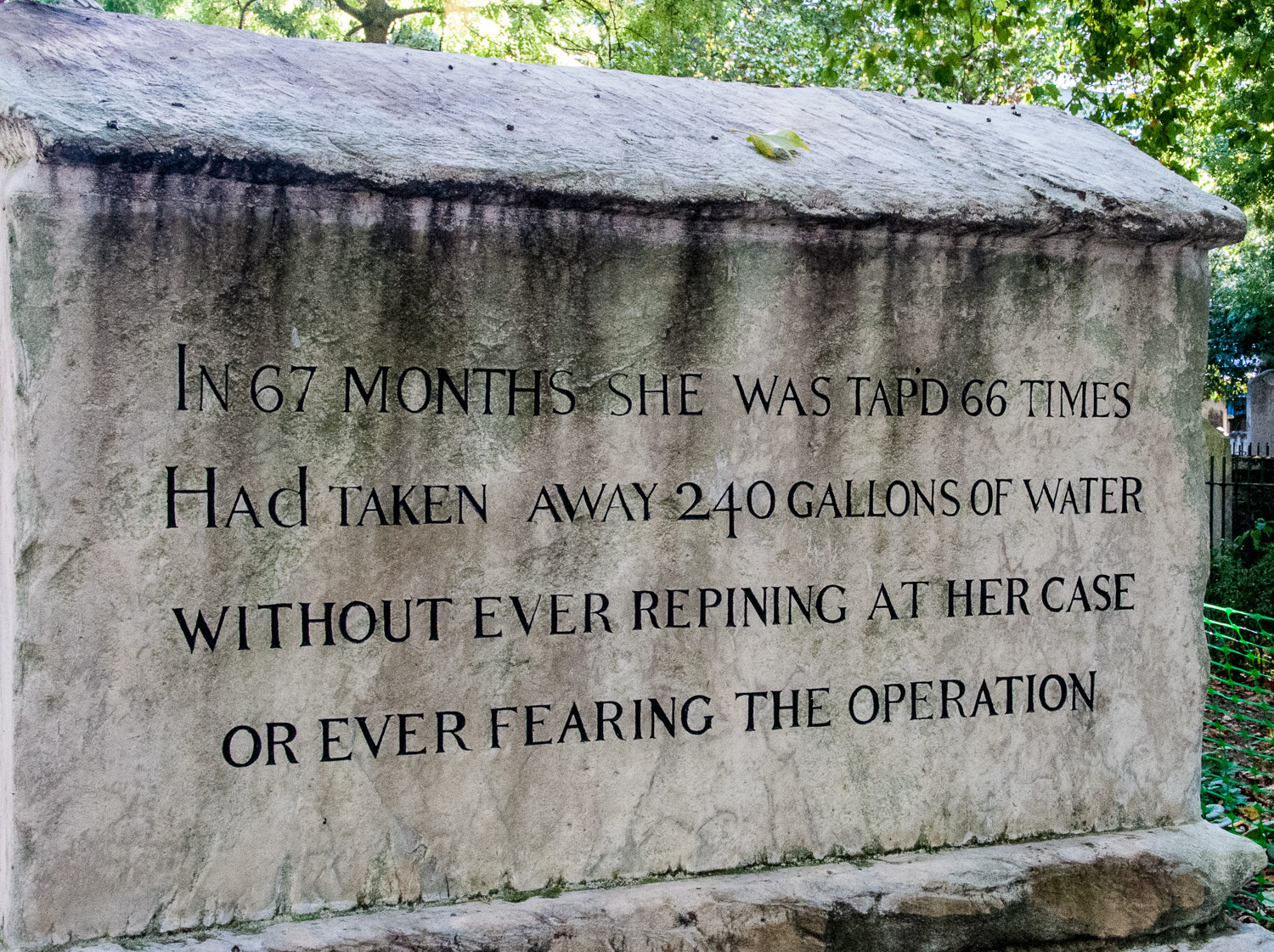

If you return to the east/west path and carry on walking you will shortly see down a path on your right the extraordinary tomb of Dame Mary Page.

It appears that Mary Page suffered from what is now known as Meigs’ Syndrome and her body had to be ‘tap’d’ to relieve the pressure. She had to undergo this treatment for over five years and was so justifiably proud of her bravery and endurance she left instructions in her will that her tombstone should tell her story. And it does …

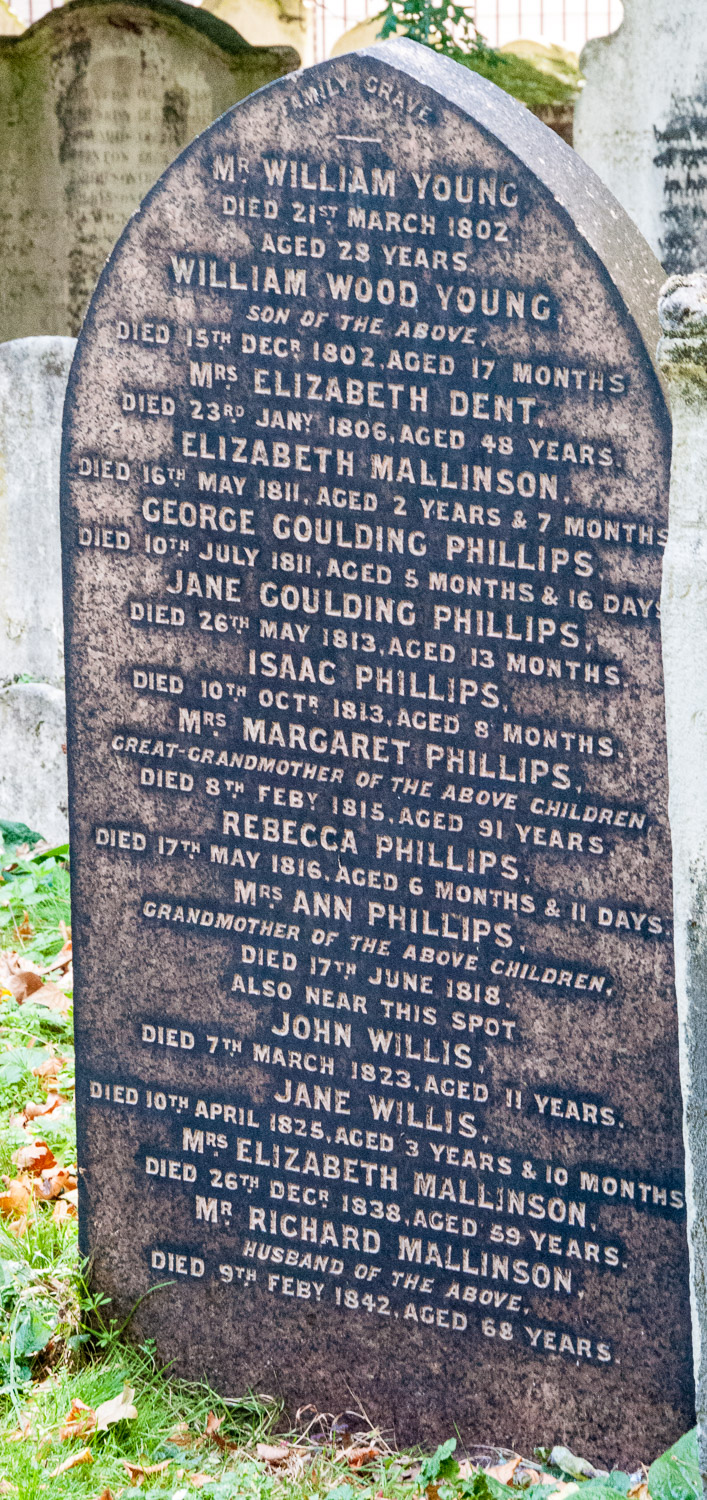

Return to the path going west and this family grave is on the left.

I mention it because it poignantly illustrates the high degree of infant mortality in the early 19th century.

Days of life are sometimes included as well as years and months

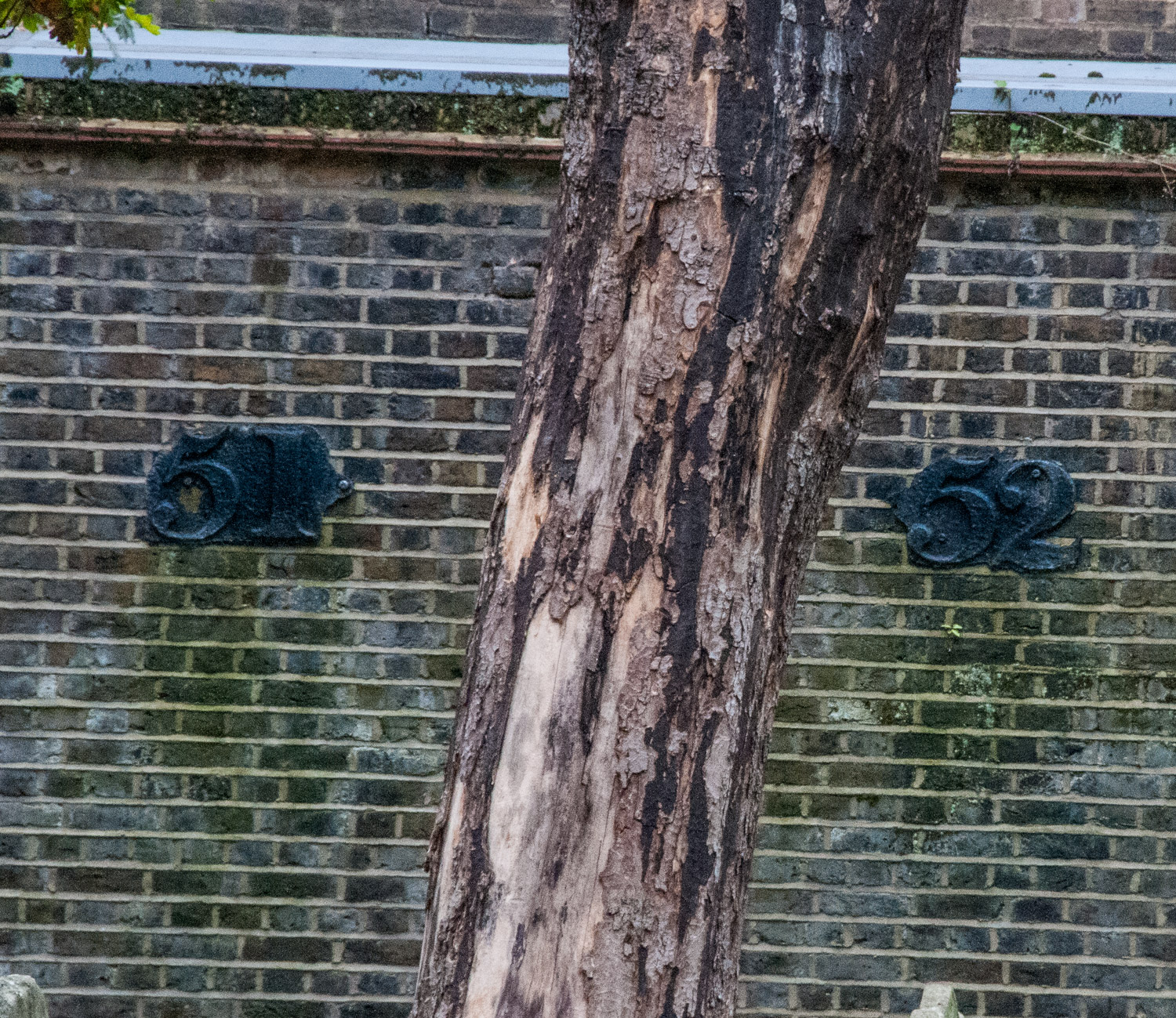

And finally, as you approach the west gate, take a look at the wall on the left and you will see the elegant iron row numbers that the Victorians placed there to make finding a particular grave easier.