The church of St Mary Woolnoth has been lucky twice.

A masterpiece by Wren’s brilliant protégé Nicholas Hawksmoor, it was built between 1716 and 1727 in the English Baroque style. Amazingly, it was scheduled for demolition in 1898 in order to facilitate the construction of Bank Underground Station. A public outcry put a stop to that and a compromise was reached. The crypt was cleared and the extended area under the church became the Underground ticket office – the church authorities collected a whopping £170,000 in compensation.

It was lucky a second time around during the Second World War which it survived unscathed …

First recorded in 1191, it has an unusual name. The founder may have been a Saxon noble, Wulfnoth, or alternatively, the name may be connected with the wool trade. Certainly this was true of the nearby church of St Mary Woolchurch Haw, destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 (its parish then united with that of St Mary Woolnoth).

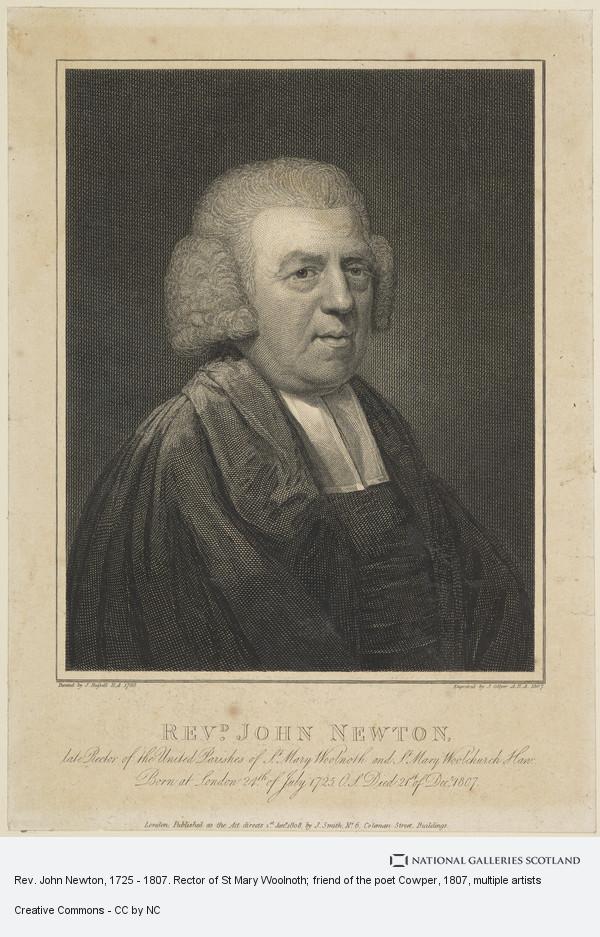

The most celebrated priest associated with the church was John Newton (1725-1807)…

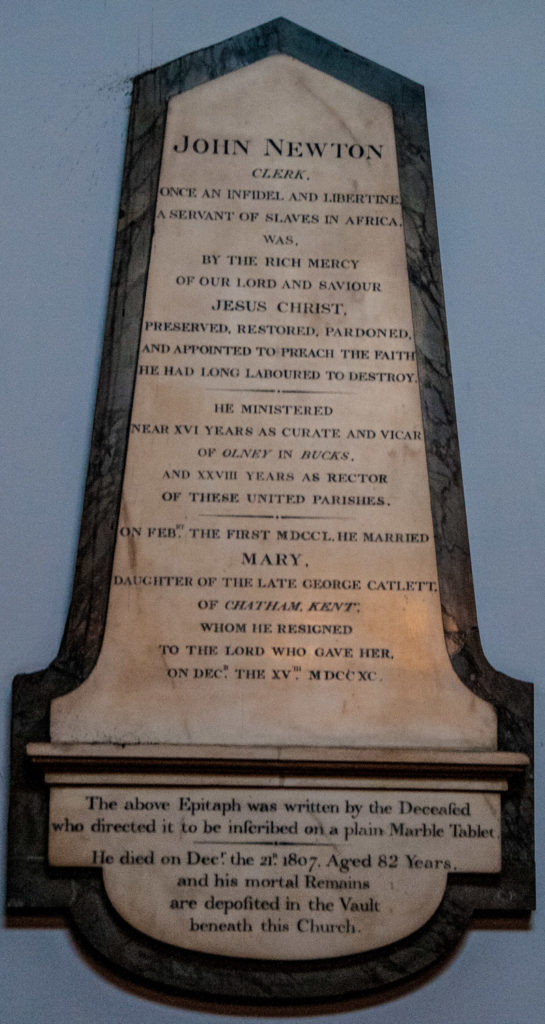

Born the son of a master mariner in Wapping, he spent the early part of his career as a slave trader. From 1745-1754 he worked on slave ships, serving as captain on three voyages. He was involved in every aspect of the slaver’s trade, and his log books record the torture of rebellious slaves. Following his conversion to devout Christianity in 1748 he eventually became rector here in 1780. In the church is his memorial tablet, which he wrote himself beginning …

John Newton, Clerk, once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in Africa …

In 1785, he became a friend and counsellor to William Wilberforce and was very influential himself in the abolition of slavery. He lived just long enough to see the Abolition Act passed into law. Think of him also when you hear the hymn Amazing Grace, which he co-wrote with the poet William Cowper in 1773.

The outside of the church is very unusual and it has a fine position on the corner of King William Street and Lombard Street, just off the major Bank road junction (EC3V 9AN). The clock is mentioned in a famous poem which I shall refer to later …

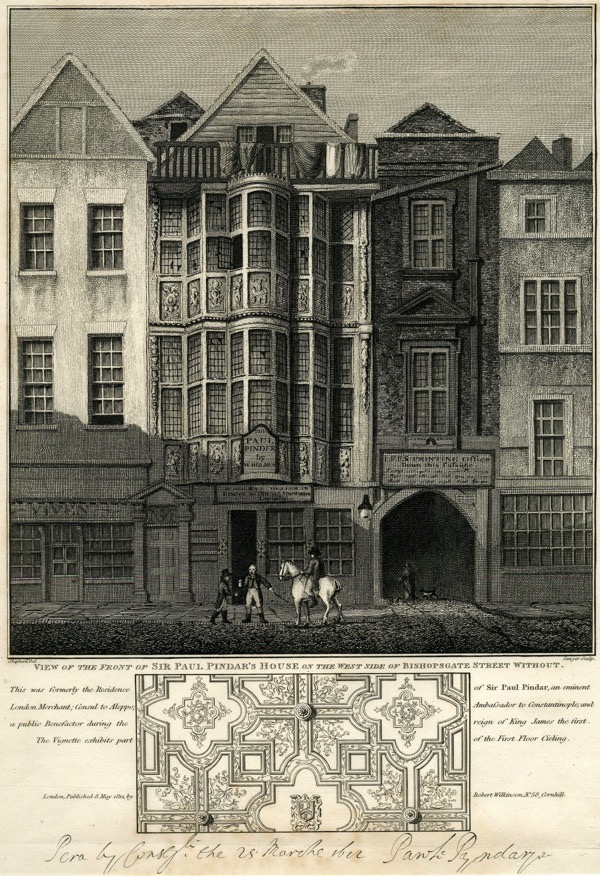

The gate to the church bears the coat of arms of the Diocese of London …

These cherubs once used to gaze at me as, when I worked nearby, I went down the steps to the station on my way home …

The small, square, tranquil interior was regarded by Simon Jenkins as the ‘most remarkable in the City, the majesty it conjures from a limited space’ ..

At each corner are a group of three great Corinthian columns …

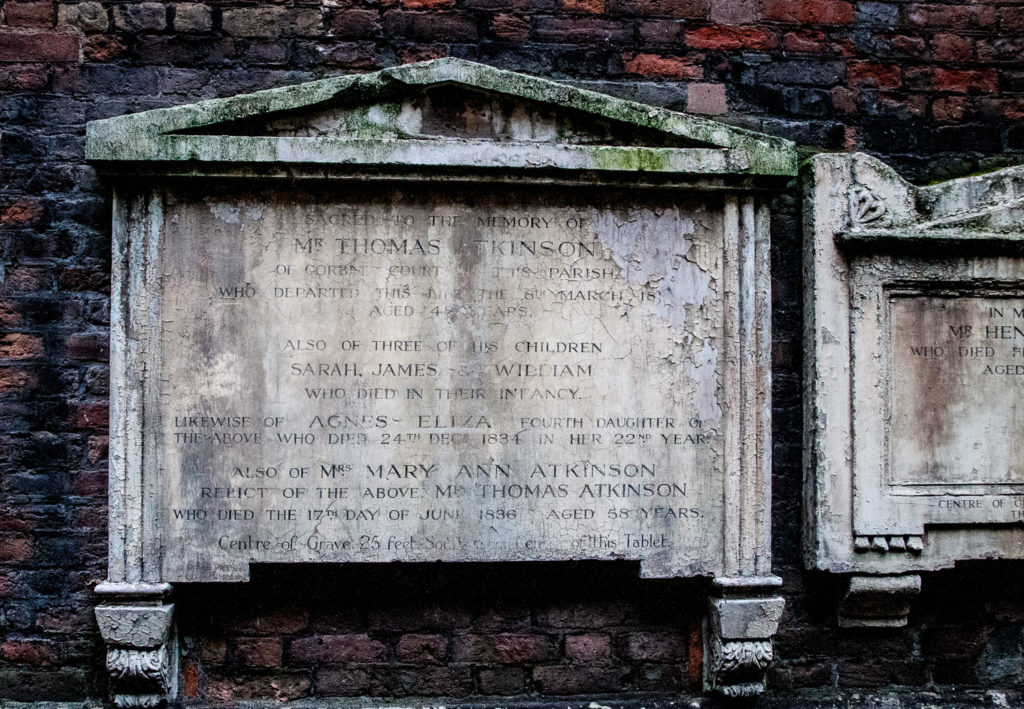

Monuments other than the one to Newton include this one to William Kentish …

The plaque, in the shape of the end of a chest tomb, incorporates a bright coat of arms with the motto ‘Survive and thrive’. William’s grandson was buried in Highgate Cemetery and the plaque describes where to find his resting place. Beneath is a note of the will of Thomas Kentish of St Albans (died 1712) which arranges for the education etc. of four boys, ideally named Kentish.

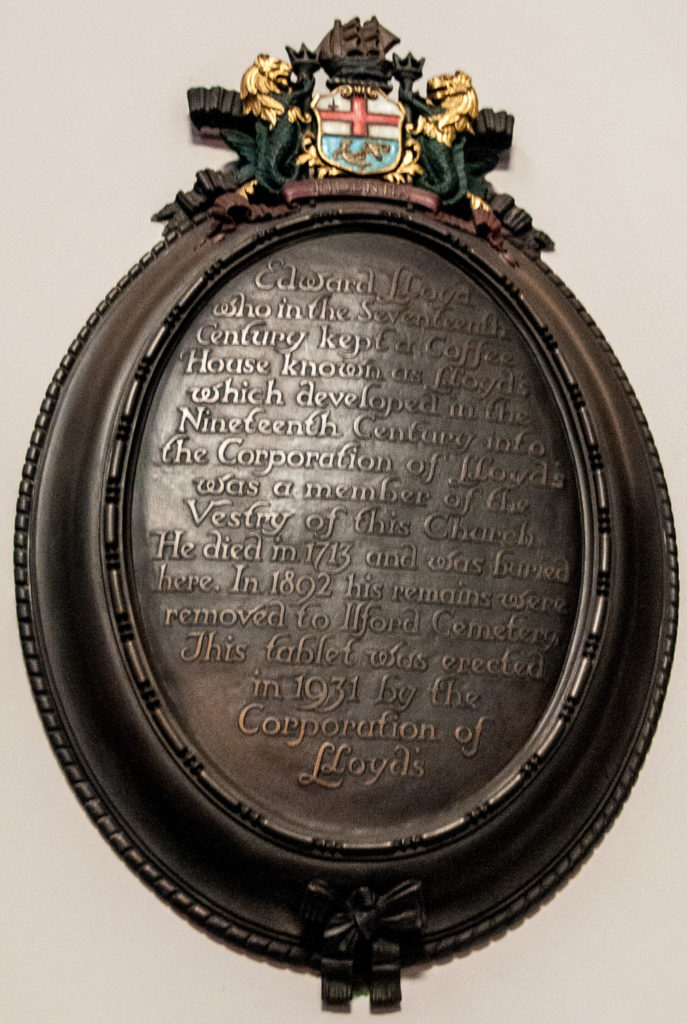

This panel was erected in memory of Thomas Lloyd, the man who started the famous coffee house, which eventually led to the Corporation of Lloyd’s …

The miniature coat of arms at the top is held by two tiny lions and, although it was placed here only in 1931, to me it does look appropriately 18th century.

The stunning, bulging pulpit dates from Hawksmoor’s time and Newton delivered his sermons from it. It was made by Thomas Darby and Gervaise Smith …

The inlaid sunburst marquetry by Appleby is sublime …

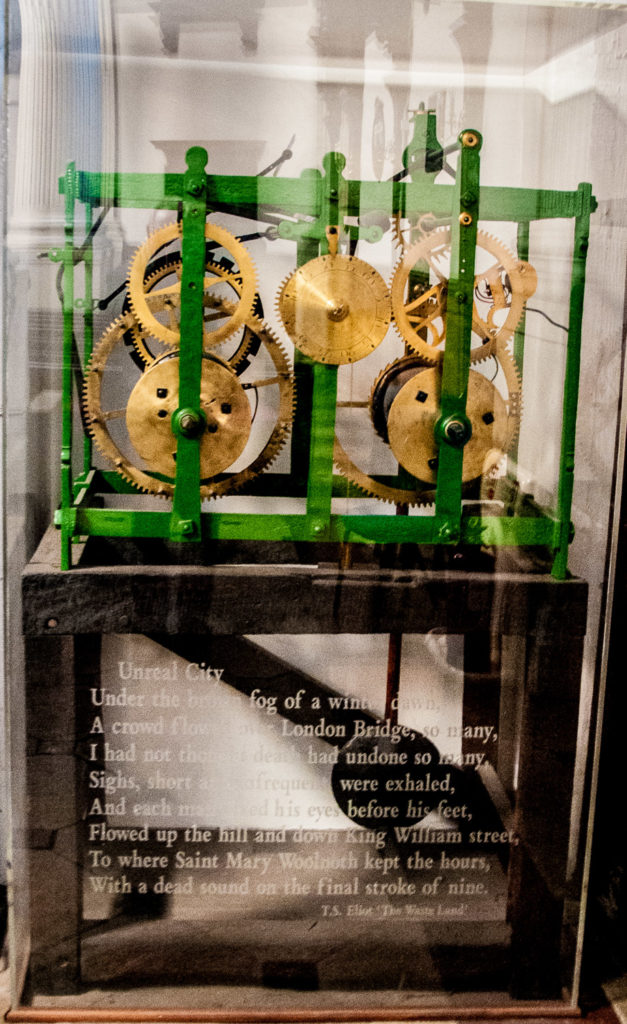

In the corner sits this clock mechanism surrounded by a cover on which is etched an extract from T.S. Elliott’s poem The Wasteland …

Elliott worked nearby and, having watched the commuters trudge over London Bridge, wrote …

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

No doubt if you were not at the office by the ‘final stroke of nine’ you were going to be late.

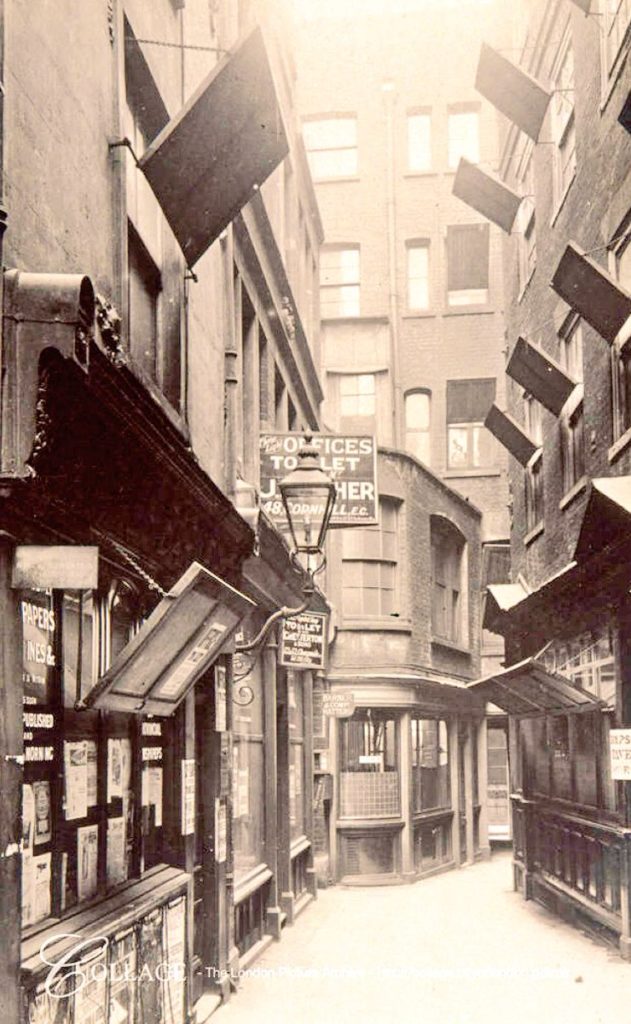

And finally, have you noticed these figures around the corner from the church in King William Street?

I used to think they were connected to the church but I was mistaken. They were, in fact, created in 1899 to enhance the entrance to the Underground Station. Bank was the terminus of the City and South London Railway – the first deep level ‘tube’ in London and, indeed, the world and the first to use electric locomotives.

Appropriately, the lady on the left represents electricity …

She wears a spiked crown, is surrounded by thunder clouds and shoots lightning bolts from her extended finger.

Mercury reclines on the right …

He represents Speed. He is wearing his winged hat and sandals and holding a caduceus. The architect was Sydney Smith who designed the Tate Gallery at Millbank and the sculptor Oliver Wheatley.

By the way, if you travel to the church by Underground, as you climb the stairs to the street take a moment to admire these fearsome dragons by Gerald Laing …

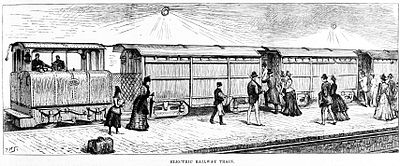

… and if you think the Tube is claustrophobic now, the original City & South London railway carriages had no windows because ‘there was nothing to see’. Here is a drawing from an 1890 edition of the Illustrated London News …