Lovat Lane, which runs between Eastcheap and Lower Thames Street, reminds one of the old City with its cobbled surface and narrow winding shape …

If you pop into St Mary-At-Hill church you will immediately encounter on your left this extraordinary representation of Resurrection on the Day of Judgment …

It’s a very unusual example of late 17th century English religious carving and most likely dates from the 1670s. Its carver is unknown, but it is known that the prominent City mason Joshua Marshall was responsible for the rebuilding of the church in 1670-74 and his workshop may have produced the relief. Exactly where it was originally positioned is uncertain; most likely it stood over the entrance to the parish burial ground and was brought inside in more recent times.

If you visit the little churchyard you will see evidence of another form of resurrection …

A plaque on the wall informs us that ‘the burial ground of the parish church of St. Mary-At-Hill has been closed by order of the respective vestries of the united parishes of St. Mary-At-Hill and Saint Andrew Hubbard with the consent of the rector and that no further interments are allowed therein – Dated this 21st day of June 1846’. Following closure, all human remains from the churchyard, vaults and crypts were removed and reburied in West Norwood cemetery. You can read more on the excellent London Inheritance blog.

I spotted this splendid winged lion outside number 31 – placed their by the owners of the Salotti 31 restaurant …

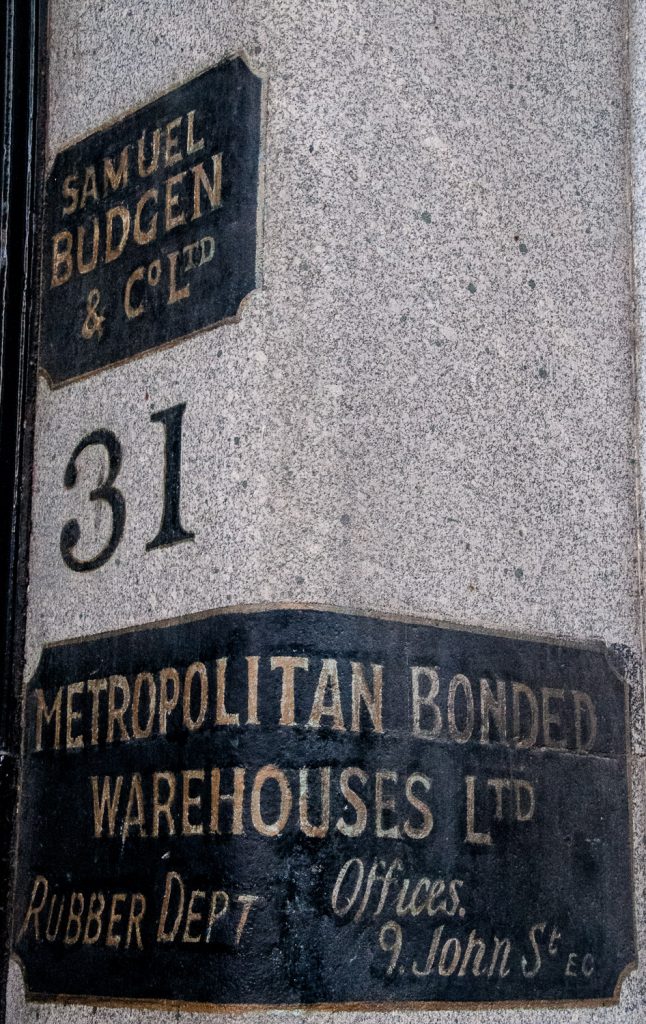

And there are some nice ghost signs …

Walking along Old Jewry last week I noticed this little courtyard …

Tucked away behind locked gates is what was once the City of London Police Headquarters (the Old Jewry address gave the force its former radio call sign of ‘OJ’). They originally moved there in 1842 but this building, in neo-Georgian style, was constructed between 1926 and 1930. The police moved out, to Wood Street, in 2001.

There are two alleys off Bishopsgate that are quite easy to miss but reward investigation. The first I explored was Swedeland Court (EC2M 4NR) …

I can’t find out why it’s called Swedeland Court (or why it’s a ‘court’ and not an ‘alley’). At the end is the interesting Boisdale Restaurant. It’s worth walking to the end and looking back towards the street as there are some charming old lamps and it’s very atmospheric …

Nearby is the rather uninviting looking Catherine Wheel Alley which will eventually lead you to Middlesex Street …

Looking back you get the true canyon effect …

The Catherine Wheel pub stood here for 300 years until it burned down in 1895. It’s said that the name was changed at one point to the Cat and Wheel in order to placate the Puritans who objected to its association with the 9th century saint. It’s also claimed that the highwayman Dick Turpin drank here, but if he drank in every pub that has since claimed a connection he would never have been sober enough to ride a horse.

When I worked near here in the 1970s it was always a pleasure to walk through this covered passage since the enclosed area was redolent with the aroma of spices, once stored here in the heyday of London Docks. It had the nickname ‘Spice Alley’ …

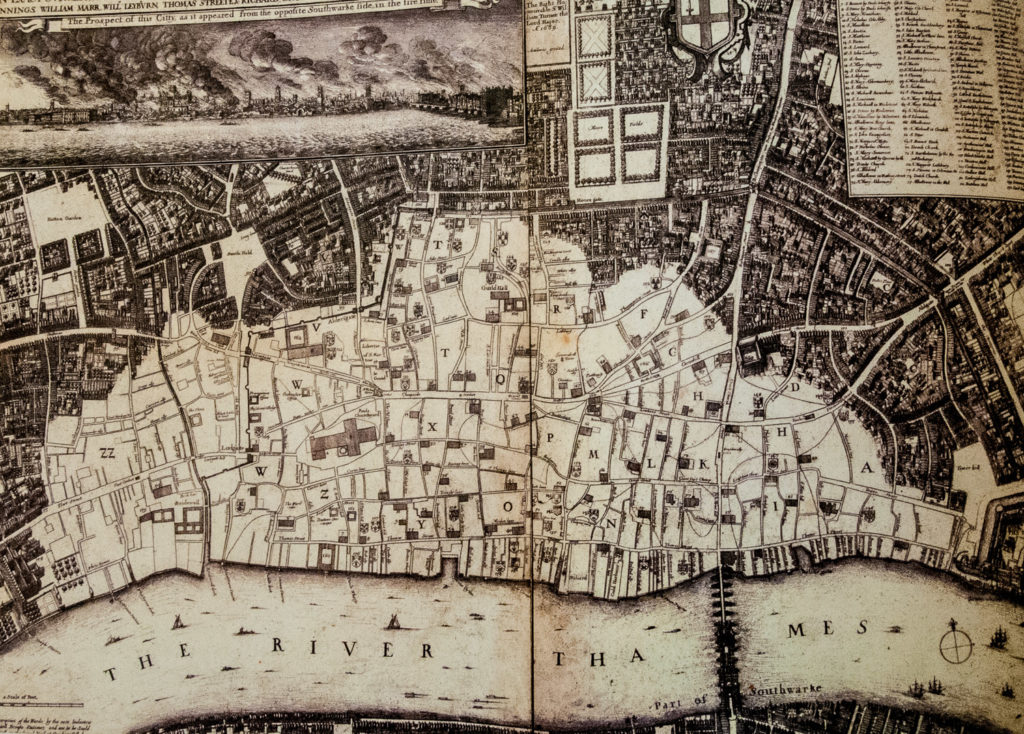

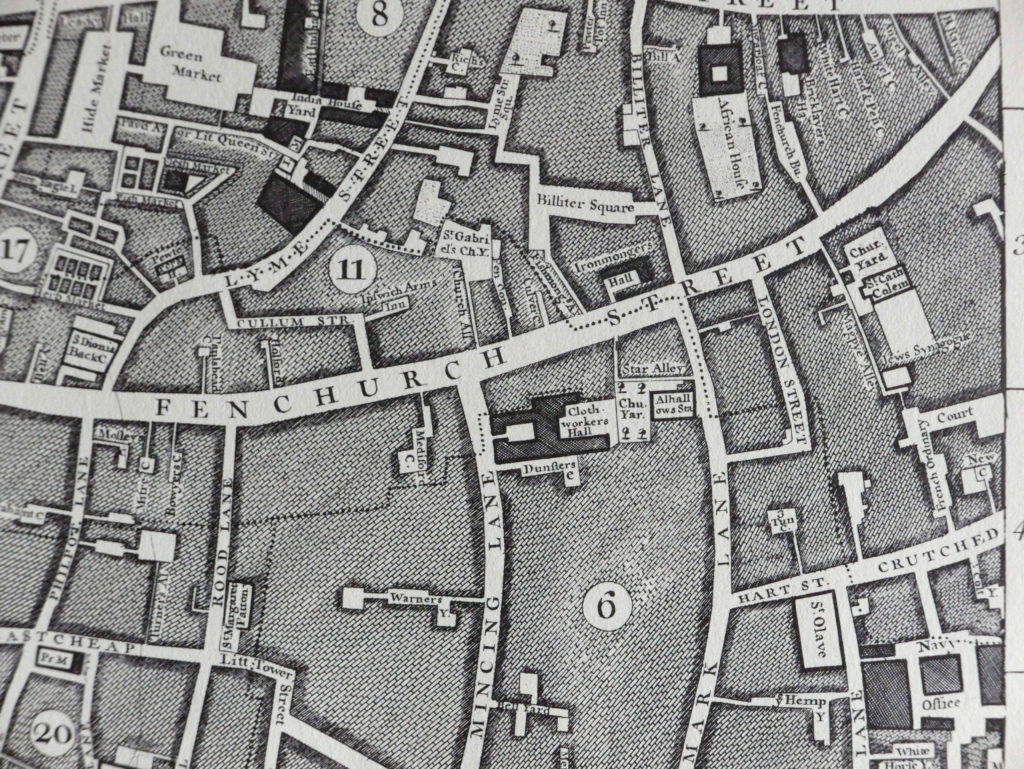

The pathway from Fenchurch Street (just beside the East India Arms EC3M 4BR) leads to Crutched Friars and by the time of Rocque’s map of 1746 it had acquired the name French Ordinary Court …

The lane itself dates from the 15th century and perhaps even earlier. It was further enclosed in the 19th century as Fenchurch Street railway station was constructed above, transforming it into a cavernous passage.

When you emerge, cross the road and look back …

The Court was named for the fact that, in the 17th century, Huguenots were allowed by the French Ambassador, who had his residence at number 42 next door, to sell coffee and pastries there. They also served fixed price meals and in those days such a meal was called an ‘ordinary’.

Star Alley (EC3M 4AJ) links Mark Lane with Fenchurch Street and you can also find it on Rocque’s map …

On the left is the tower of All Hallows Staining …

First mentioned in the late 12th century, ‘staining’ meant it was made of stone unlike other City churches which were made of wood. It was rebuilt in 1674 after collapsing four years earlier (possibly because of too many burials near the building). You can read more about it here in the London Inheritance blog.

I found a few odd things here. These mysterious tiles, which look quite modern, have what I think are construction workers in the foreground and a tower crane in the background …

And this spooky little alien character …

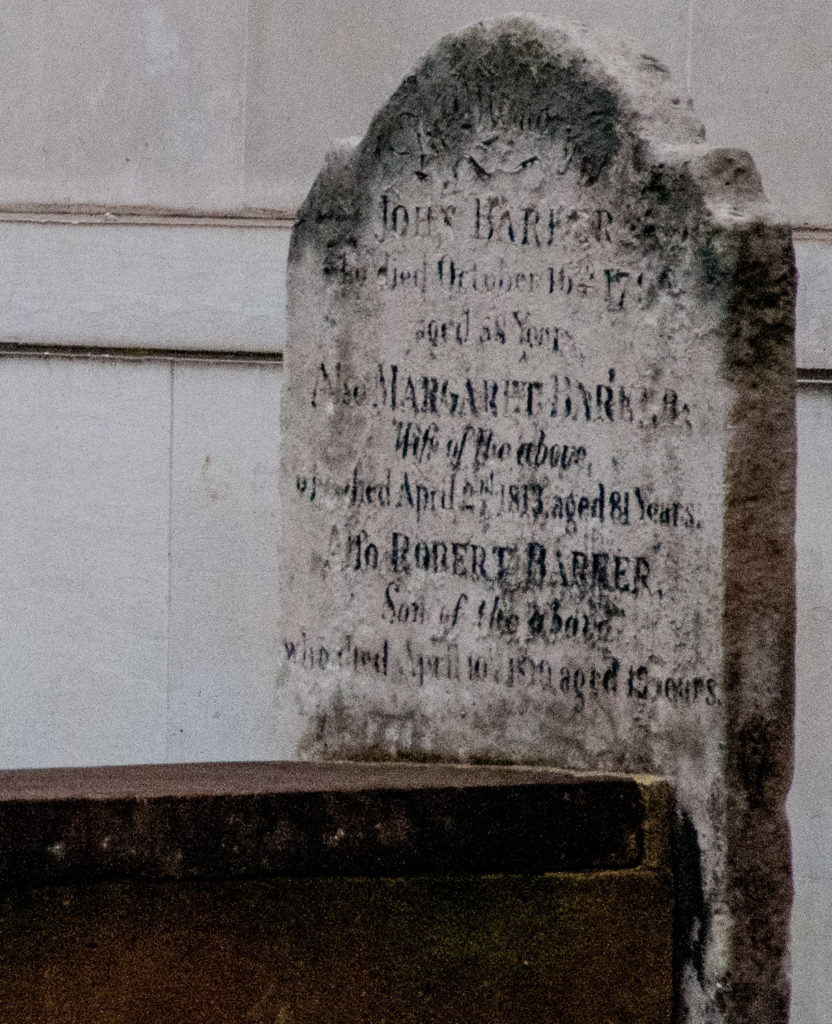

There is one grave left in the graveyard …

Unfortunately I have not been able to find out more about the family.

As you look towards Fenchurch Street, you can see the date of the post-war building inscribed above the entrance …

Finally, there is also an edition of Spitalfields Life dealing with City Alleys – you can access it here. This is my favourite picture from it …