‘I have emptied a cesspool, and the smell of it was rose-water compared with the smell of these graves.’ So declared a gravedigger during an 1842 enquiry into the state of London’s graveyards, a problem acknowledged even in Shakespeare’s day …

‘Tis now the very witching time of night

When churchyards yawn, and hell itself breathes out

Contagion to this world.

(Hamlet’s soliloquy Act 3 Scene 2)

Fear of the ‘miasma’ and cholera eventually led to legislation being passed to prohibit new interments and allow graveyard clearance.

Despite the fact that widespread use of City churchyards as burial grounds ceased over 150 years ago, the remaining sites often still carry an atmosphere of serenity and a link with Londoners long deceased. These folk lived, worked and died here and played their part in the City we see today. Despite fires, war and redevelopment, some still rest here, although bones and stones may have long been separated.

So this is a short journey showing a few of these places before and after the Second World War and what remains of memorials to previous ‘residents’.

First up is my local church, St Giles Cripplegate, which has many connections with the famous. Oliver Cromwell was married here, it is the final resting place of John Milton and two of Shakespeare’s nephews were christened here. Sadly the church was badly damaged in the war and the graveyard almost completely destroyed.

Here is how it looked in 1815 …

Painting by George Shepherd.

And how it looks now …

In the shadow of the Barbican Estate – tombstones are incorporated into the seating on the right.

Some memorials can still be read … …

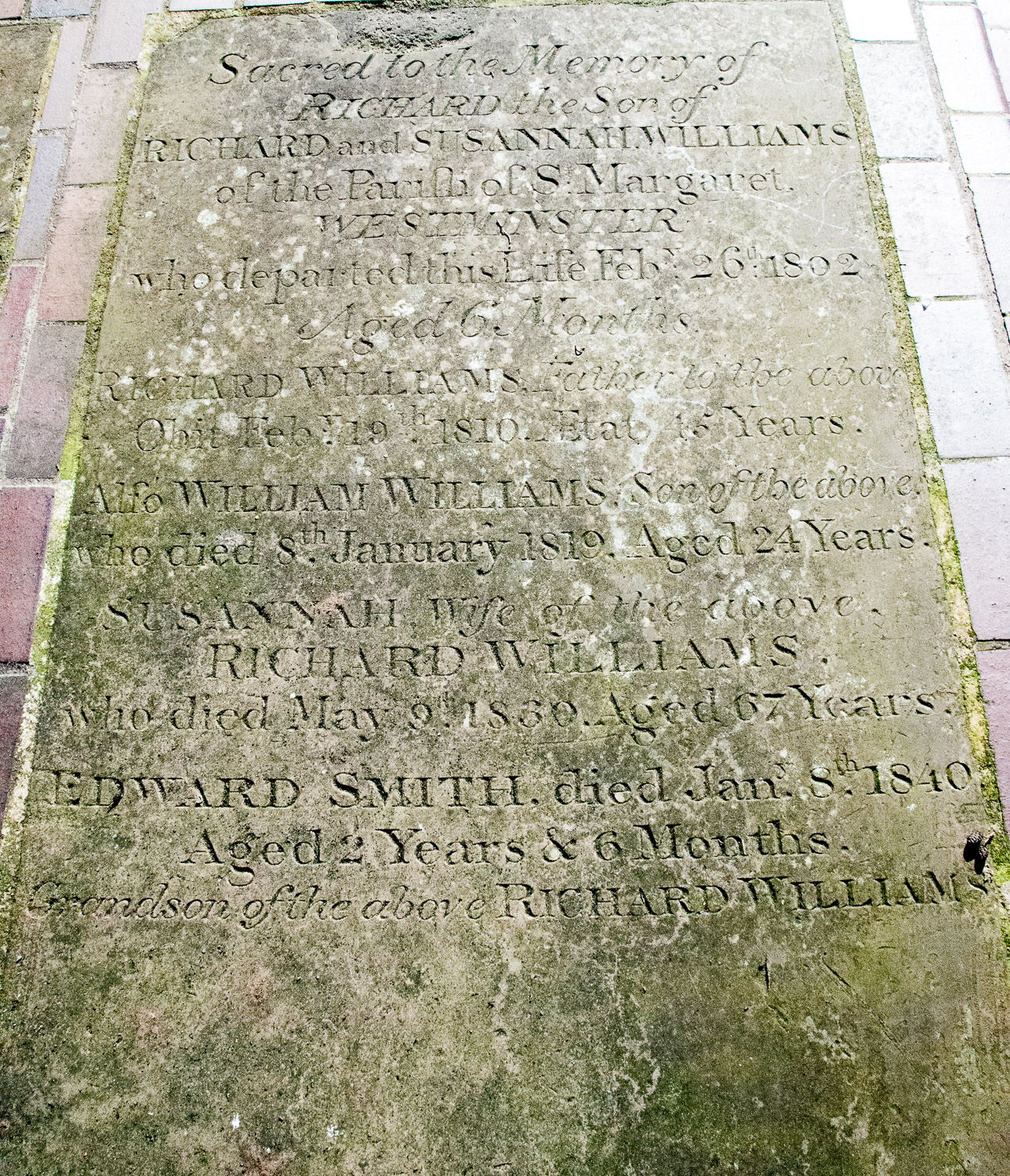

The Williams Family gravestone.

The deaths in the Williams family, recorded over the years 1802 to 1840, give typical examples of the high incidence of child mortality.

Some other memorials have traces of their original decoration …

Virtually all the other stones are badly eroded and the inscriptions illegible.

The magnolia trees in the grounds look lovely at the moment – there are some very old barrel tombs laid out in the background.

Nearby in Smithfield, St Bartholomew the Great, the oldest church in the City, survived the Great Fire of 1666 and two World Wars and would be on my must-see list for anyone interested in church architecture.

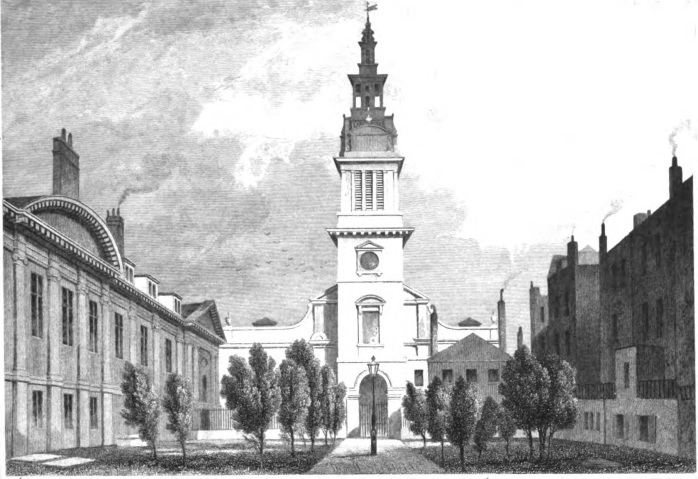

The graveyard was in constant use until the 1840s …

St Bartholomew the Great 1737 – British History Online

The graveyard space has been tidied up. This memorial rests against the wall …

Memorial stone for George Hastings who died in 1816 aged thirty years. The dark marks are stains on the stone, not the shadows of two scotch terriers!

The site now looking towards the church …

Designed by Wren and completed in 1704, Christ Church Greyfriars, on the corner of Newgate Street and King Edward Street, looked like this in the 1830s …

Christ Church Greyfriars, as depicted in London and its environs in the nineteenth century by James Elmes (1831) (image via Wikimedia Commons). Source : Flickering Lamps website.

On the night of 29 December 1941, incendiary bombs created the ‘Second Great Fire of London’, and Christ Church was one of its victims …

Firefighters in the smouldering ruins (image from the Citizens’ Memorial).

These walls and the tower are all that remain but are laid out as a very attractive garden …

The wooden towers within the planting replicate the original church towers and host a variety of climbing plants.

You can read more about this and other churches in my 28 December 2017 blog The City’s lone church towers and the Blitz.

When graveyards were cleared it became common practice over the years to line up old memorials against the wall …

Stones in Postman’s Park, the churchyard of St Botolph’s Aldersgate.

As always, St Vedast alias Foster in Foster Lane EC2 is worth a visit …

The tranquil Fountain Courtyard and Cloister.

Overlooking the little garden is this memorial …

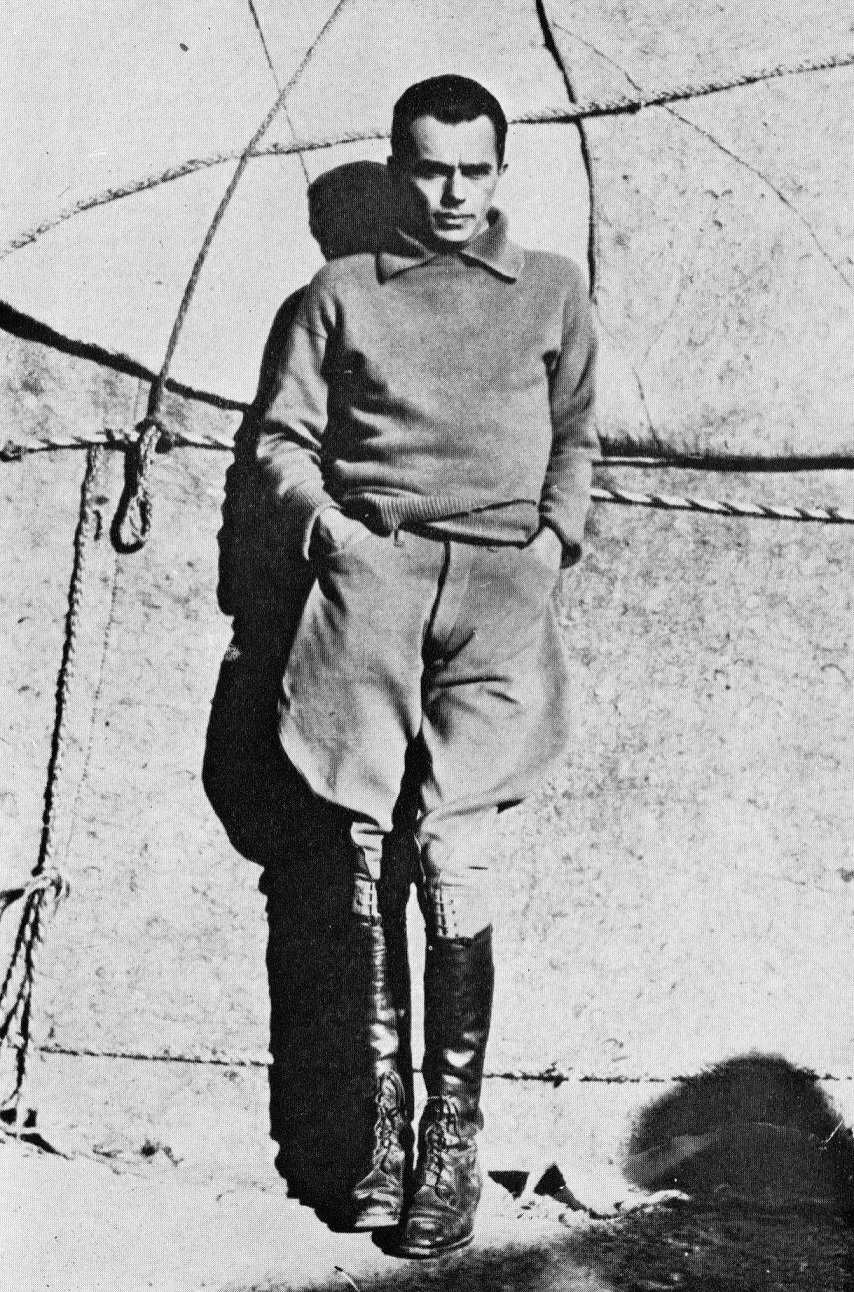

As far as I can discover, ‘Petro’, as his friends called him, was a White Russian who had taken French nationality. He became a member of the Special Operations Executive and, being a supporter of the Free French, he joined the Volunteers in December 1941 and was subsequently wounded in action.

I have been unable to find out any more, which is a shame since he obviously led an extraordinary life. I have managed to find a picture of him though …

The Courtyard also displays a nice boundary marker …

Boundary marker for St Vedast alias Foster.

And finally, the church that rose again …

St Mary Aldermanbury in the 19th century.

The church was almost completely destroyed in the Blitz, but in 1966 its surviving remains were shipped to Fulton, Missouri, and rebuilt in the grounds of Westminster College. The reconstructed church stands as a memorial to Winston Churchill who made his Sinews of Peace speech in the College Gymnasium in 1946. It became famous for the phrase ‘From Stetin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent’.

St Mary Aldermanbury in its new home …

There is now a garden in the footprint of the old church at the junction of Aldermanbury and Love Lane. It contains a memorial to the actors Henry Condell and John Heminge who preserved Shakespeare’s works in the First Folio and who themselves were buried in the church. There is also a majestic bust of the Bard himself …

The sculptor was Charles John Allen and the work created in 1895.

The garden on the original site of St Mary Aldermanbury.