The idea of an embankment along the Thames was first suggested by Sir Christopher Wren after the Great Fire of 1666 and work eventually began in 1861 under the control of Sir Joseph Bazalgette the Metropolitan Board of Works’ Chief Engineer. Its purpose was not only to ease congestion but also to house the main sewer and it was opened on 13 July 1870 by the Prince of Wales. The total area of land reclaimed was over 37 acres and about 20 acres of this were laid out as gardens and these were the objective of my walk last week.

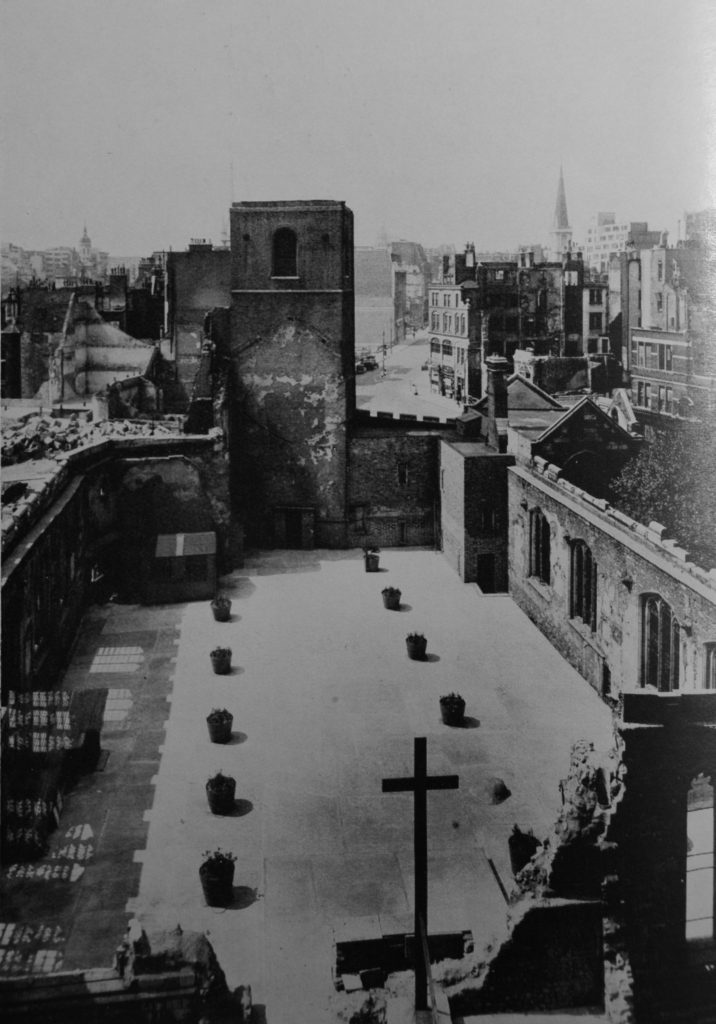

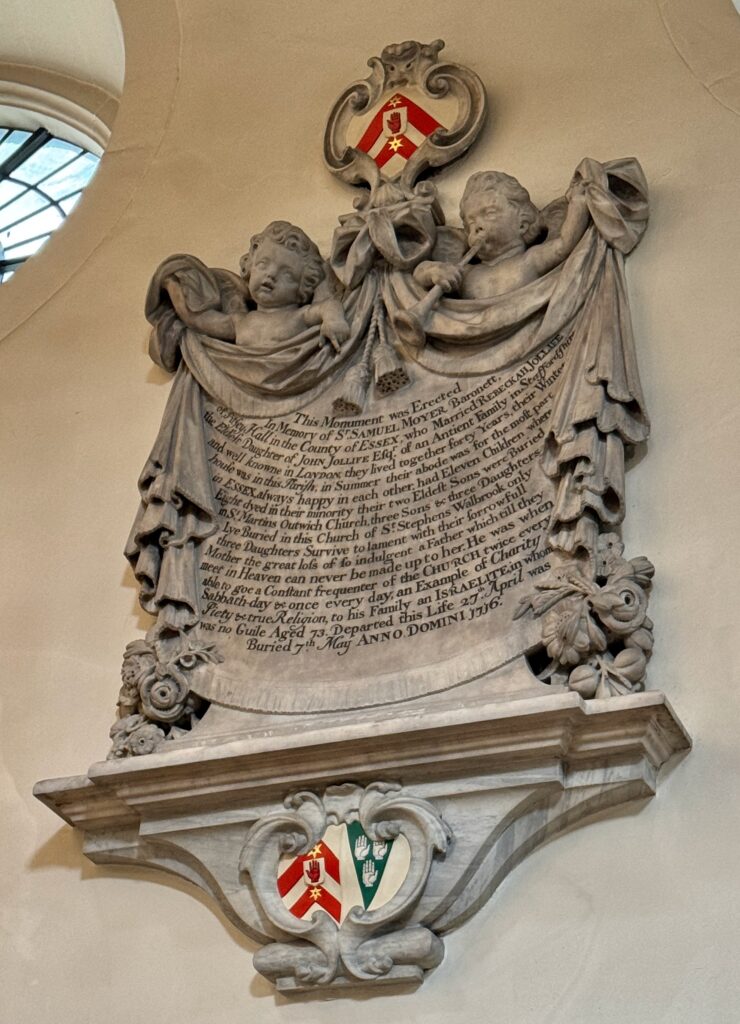

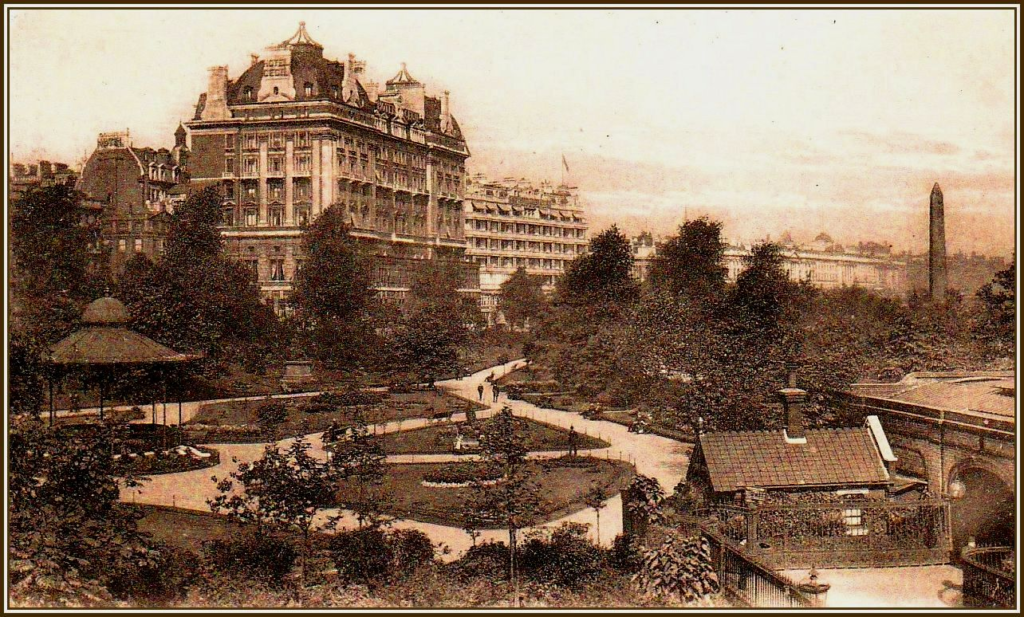

The gardens shortly after opening …

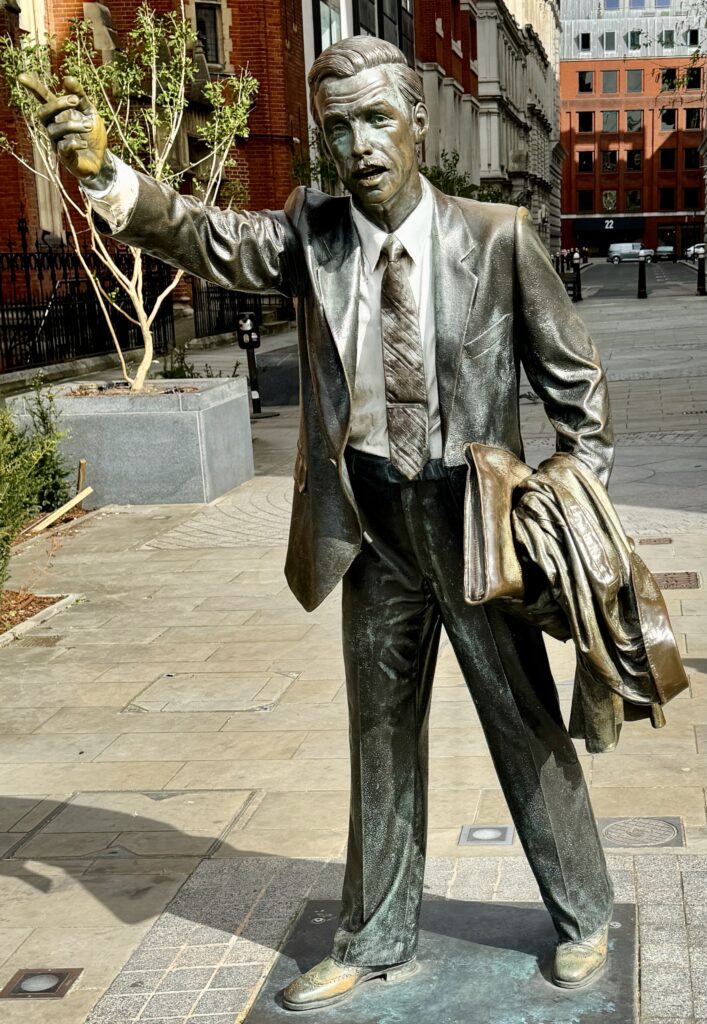

Walking west from Blackfriars I encountered one of my favourite pieces of street sculpture …

He’s had a tough day at the office and now just wants to get home but, sadly, he’s been trying to grab that cab since 2014. Sculpted by J. Seward Johnson Jr. in 1983, it originally stood on Park Avenue and 47th Street in New York. It’s called, not surprisingly, Taxi!

A little further west are the gates to the Temple private gardens – haunt of the legal profession.

The flying horse Pegasus is the emblem of Middle Temple …

The badge of the Middle Temple consists of the Lamb of God with a flag bearing the Saint George’s Cross …

I walked past the two formidable dragons symbolising the entrance to the City of London …

Seven feet high, they were once mounted above the entrance to the Coal Exchange which was demolished between 1962 and 1963.

They were cast by London founder, Dewer, in 1849 as can be seen on the back of the shield …

Alongside the dragon on the north side of the road is a tablet commemoration Queen Victoria’s last visit to the City in March 1900 …

Time now to enter the first of the gardens and to admire the memorials erected to the great, the good and the brave.

This is the Lady Henry Somerset Children’s Fountain. She was elected president of the British Women’s Temperance Association in 1890 and during her time with them its political and social influence grew. She promoted many endeavours, including the use of birth control, as she argued that sin begins with an unwelcome child …

The formidable Lady Somerset …

What I also discovered in my research was that she outed Lord Henry as a homosexual (a crime during the 1800s), which resulted in their separation and her gaining custody over their son. As a result of publicising his sexual orientation, she was ostracised from society since in those days women were expected to turn a blind eye to every kind of their husband’s infidelity. His lordship decamped to Italy.

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (1842-1900) was a composer and most famous for his collaborations with the librettist Sir William Schwenck Gilbert (1836-1911). Their collaboration resulted in fourteen Comic Operas a number of which are still frequently performed today by both amateur and professional companies to the delight of people around the world …

His memorial features a bust atop of a pedestal together with a weeping Muse of Music. The plinth also carries lines from Gilbert and Sullivan’s 1888 opera The Yeomen of the Guard: “Is life a boon? / If so, it must befall / That Death, whene’er he call, / Must call too soon”.

The lines are repeated in the bronze sculpture at the base, which depicts an open book of music, one of the masks of Comedy and Tragedy and a mandolin …

Apparently the statue has been described as ‘the most erotic in London’.

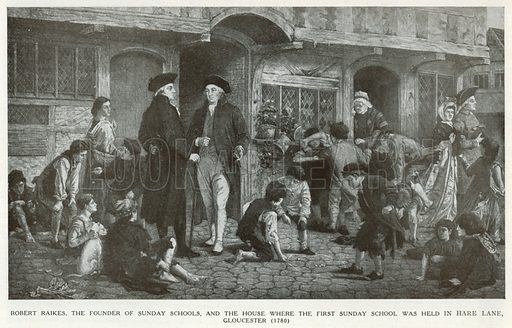

Robert Raikes, pioneer of Sunday Schools …

Although Sunday schools were not original to Robert Raikes – they were in existence many years before he started his first in 1780 – it was he who put them on the map and whose efforts gave huge momentum to the movement in Britain. Hence, when in 1880 this memorial was erected to celebrate the centenary of the Sunday school movement, the statue featured Robert Raikes. Read more about this fascinating man here.

The flower beds are wonderful …

The Henry Fawcett memorial ‘erected by his grateful countrywomen’ …

Henry Fawcett was an economist and politician who was held in high regard by the public. He was born in 1833 and educated at the University of Cambridge. At the age of 25 he was involved in a shooting accident that left him blind. However, he refused to let his affliction dampen his life and ambitions. He rose to become a Professor in Economics at Cambridge University and was elected Member of Parliament for Brighton in 1865 to 1874, and subsequently for Hackney in 1874 to 1884. In 1880 he was also appointed the position of Her Majesty’s Postmaster-General. He introduced improvements in the Post Office such as the parcel post, postal orders and sixpenny telegrams. He was also an avid supporter of women’s rights and encouraged the Post Office to employ women. He married the renowned suffragist, Millicent Fawcett, in 1867.

More lovely flowers with the memorial to Lord Cheylesmore in the background …

This statue is in tribute to Sir Wilfrid Lawson, the 2nd Baronet probably best known as a temperance campaigner and radical, anti-imperialist wing of the Liberal Party. The statue depicts Lawson, standing as if about to speak while a member of parliament …

He was an extraordinary character and you can read more about him here.

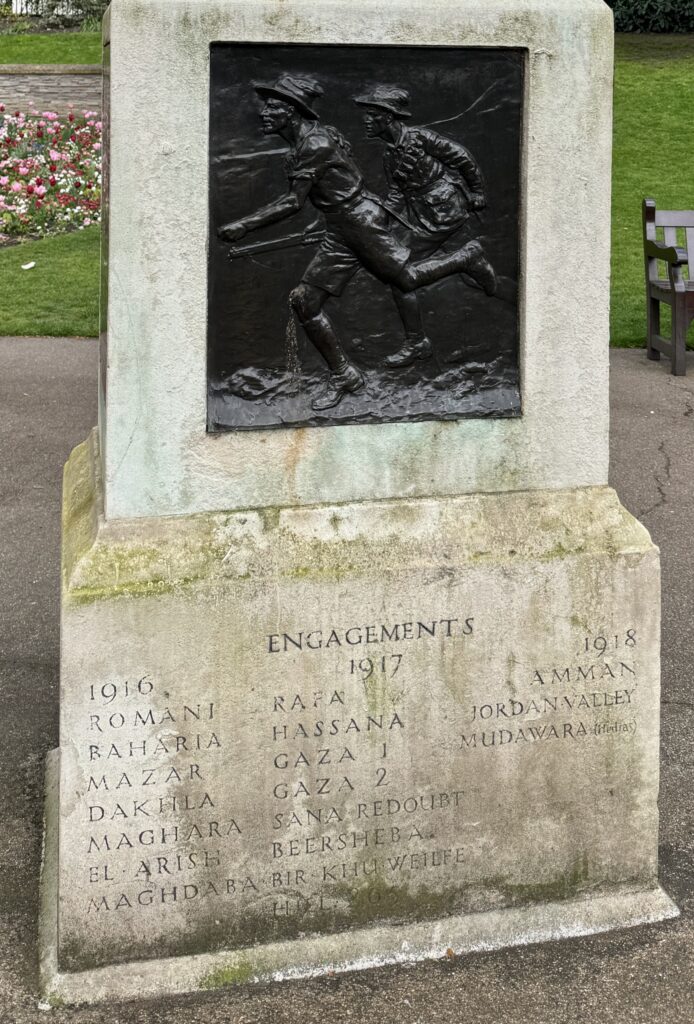

I have always been fascinated by this memorial to the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade …

Do take a few minutes to read this article about them from the 20th Century Society Journal:

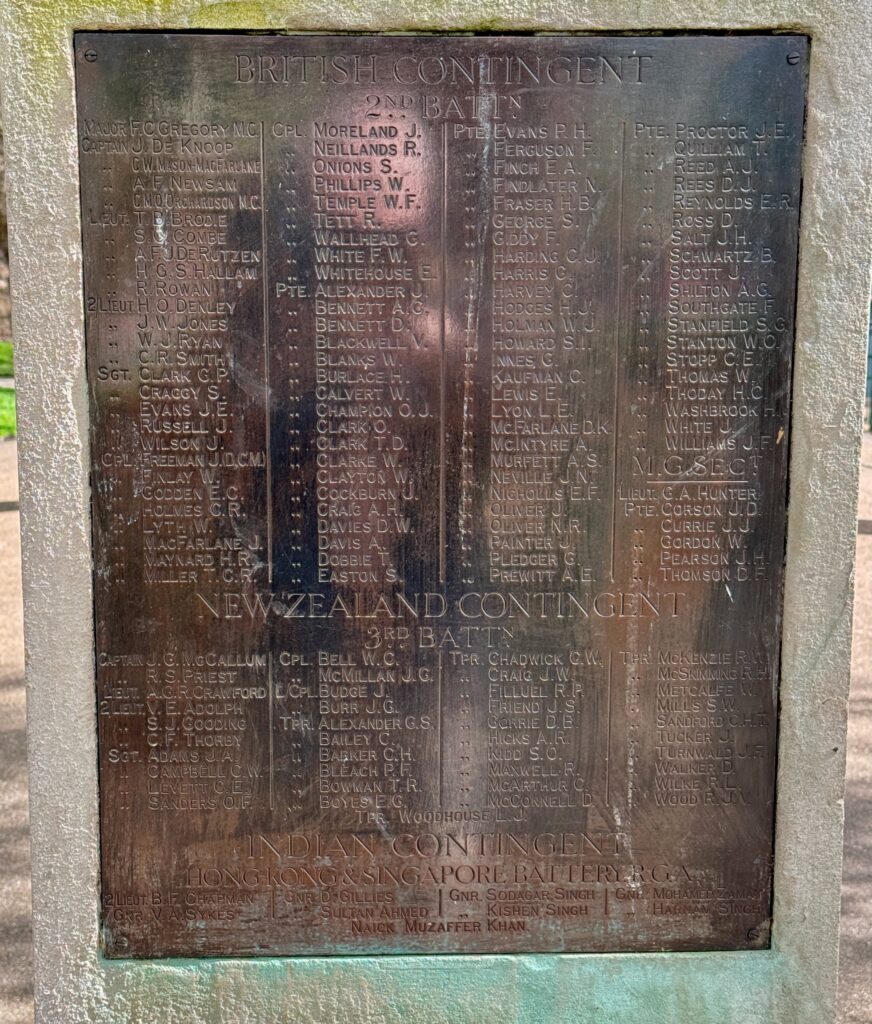

The Imperial Camel Corps were formed to patrol the western desert in the First World War and fought major campaigns in Egypt, Sinai and Palestine. Their job was to protect Allied troops (evacuated after the failure at Gallipoli) from risings by the Ottomans and Senussi confederation of tribes. The Senussi were eventually forced into submission late in 1916 by starvation, and by being denied the use of wells by camel corps units and light car patrols. The Camel Corps’ most famous moment was assisting Lawrence of Arabia to capture Jerusalem in the rebellion of 1916-18, although the damper weather meant many animals became victims of sarcoptic mange. The majority of the Infantry were Australian, some of whom were already experienced camel jockeys. The corps were so successful that they were expanded from four to eighteen companies. Six companies were formed from British Cavalry, two from New Zealand Cavalry. The corps were reorganised into four large battalions to fight the Turks, assisted by an artillery unit from Hong Kong and Singapore.

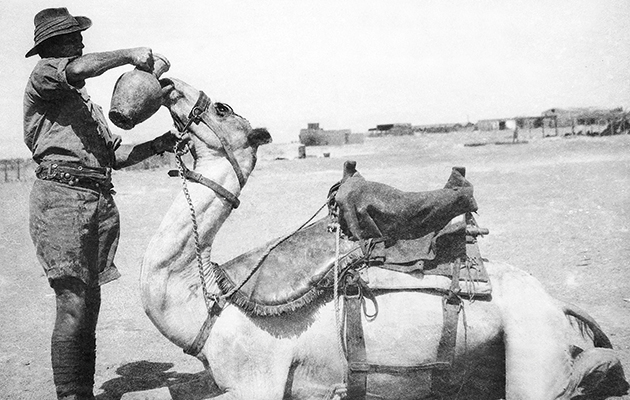

Always look after your camel …

A World War One Anzac Australian Camel Corps soldier giving his camel a drink of water from a chattu vase, 1916. You can find more images here and here.

By the end of the war 346 of their formation had died in action. The reality of the ultimate sacrifice, the names behind the numbers …

The nearby York Watergate is almost 400 years old. It was built in 1626 in the grounds of York House as a mooring point for the Duke of Buckingham’s boat or the boats of guests. As a result of the building of the Embankment, the river is now over 150 yards away …

The watergate around 1850 …

More flowers – couldn’t resist taking pics …

And now to more recent conflicts. These memorials are located at the far west end of the gardens near Westminster Underground Station.

The Korean War …

Iraq and Afghanistan …

‘The boldest measures are the safest’ – The Chindit Memorial …

The Fleet Air Arm …

And finally, Queen Boudicca and her daughters tower over the tourists …

Wasn’t I clever to catch that seagull in flight!

Remember you can follow me on Instagram …