Where do you think this pretty marble fountain is located?

And Italian piazza? A rather posh park? A country house garden?

A little boy holds a goose’s neck from whose mouth water would flow if the fountain was working …

The big surprise about its location is apparent when you gaze upwards …

This is Adam’s Court and you gain entrance from either Old Broad Street or Threadneedle Street. This is the entrance from the former …

The elegant clock above the entrance is supported by two fishes. Unfortunately it’s not working and the glass has got rather grubby …

Shortly after entering you will see these attractive wrought iron gates bearing the initials NPBE and the date 1833. The initials refer to the National Provincial Bank of England which was founded in that year …

Further on is a totally unexpected green open space (alongside which is the little boy’s fountain) …

If you carry on and exit on to Threadneedle Street and look back you will see another set of ornate gates …

These are 19th-century, and were originally for the Oriental Bank. The grand building with the arch in the background was also part of the Bank, but the building was later taken over by the neighbouring National Provincial Bank, and their monogram added.

Look at the spandrels above the window … …

Two men are holding the reins of two camels.

Across the road from Adam’s Court on Old Broad Street is the enticing entrance to Austin Friars …

Before you cross the road, look right and admire the old City of London Police call box which has retained its flashing light indicating a caller was in need of help …

Walking through Austin Friars you pass a studious monk, writing in a book with his quill pen …

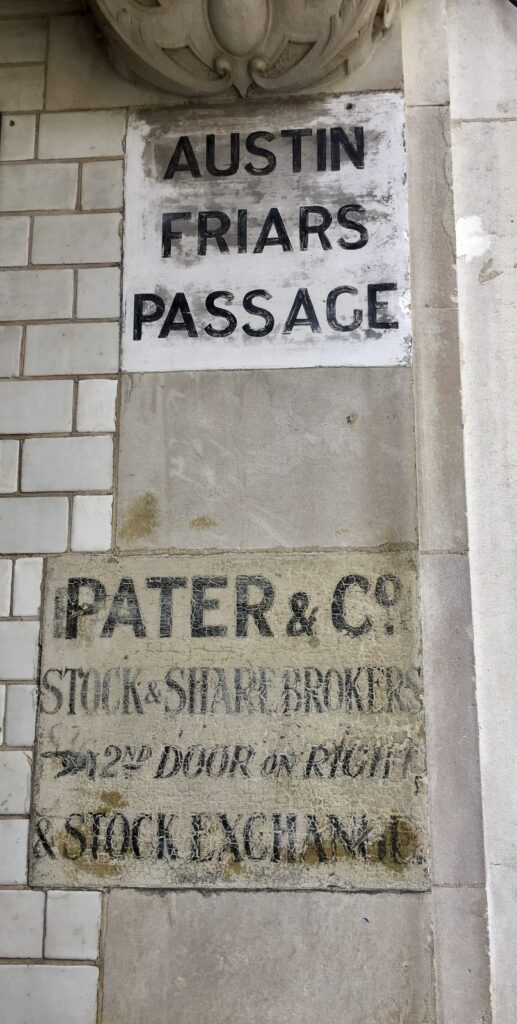

Eventually in front of you is the tucked away entrance to the atmospheric Austin Friars Passage, where I came across my next big surprise …

Almost at the end I encountered an extraordinary sight, a bulging, sagging wall that was clearly very old …

Up high is a parish marker for All Hallows-on-the-Wall, dating to 1853 …

But the wall looks even older and, sure enough, standing in the alcove that leads to the other side and looking up, I saw this …

Another parish marker dating from 1715 – from the since-demolished church of St Peter le Poer. What a miracle that this old wall (which is not listed) has survived for over 3oo years as new buildings have sprung up all around it.

Look up and you’ll see that one of those buildings has a particularly scary fire escape. I wouldn’t fancy running down that in a panic …

As you leave you can admire the charming ghost sign for Pater & Co …

The company was run by Arthur Long and Edgar John Blackburn Pater and traded from the 1860s to 1923 when Long retired and Pater continued on his own.

As is often the case I am indebted to the excellent Ian Visits blog for some of my background information. Here are links to Ian’s comments on Adam’s Court and Austin Friars Passage.

My earlier blogs on courtyards and alleys can be found here and here.

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …