In a grim courtyard outside the gruesome Baynard House on Queen Victoria Street (EC4V 4BQ) is the quite extraordinary sculpture The Seven Ages of Man by Richard Kindersley (1980) …

At first the infant – mewing and puking in the nurse’s arms …then the whining schoolboy creeping like a snail unwillingly to school … then the lover … then a soldier full of strange oaths …

… and then the justice full of wise saws … then the sixth age …the big manly voice turning again toward childish treble, pipes and whistles in his sound … then second childishness and mere oblivion, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

(Jacques in Shakespeare’s As You Like It Act II Scene vii)

In my local church, St Giles-without-Cripplegate (EC2Y 8DA), there are a set of busts that I have always admired that are on loan from the Cripplegate Foundation. They were presented by J Passmore Edwards (1823-1911), the journalist and lifelong champion of the working classes. His bequests can still be seen today throughout the country and included 24 libraries and numerous schools and convalescence homes.

Oliver Cromwell married Elizabeth Bourchier here in 1620. His bust portrays him ‘warts and all’ just as he preferred …

John Milton, the poet and polemicist, was buried here in 1674. By 1652 he had gone completely blind, probably from glaucoma, as is obvious from this representation …

All the Passmore-Edwards busts in the church are by George Frampton (1860-1928).

Miraculously, the church tower survived World War II bombing. It dates from the 1394 rebuilding of the church and at the base there is some of the original stone from 1090. The unusual upper part of the tower dates from the 17th century and overall provides an interesting contrast with the soaring 20th century Barbican development …

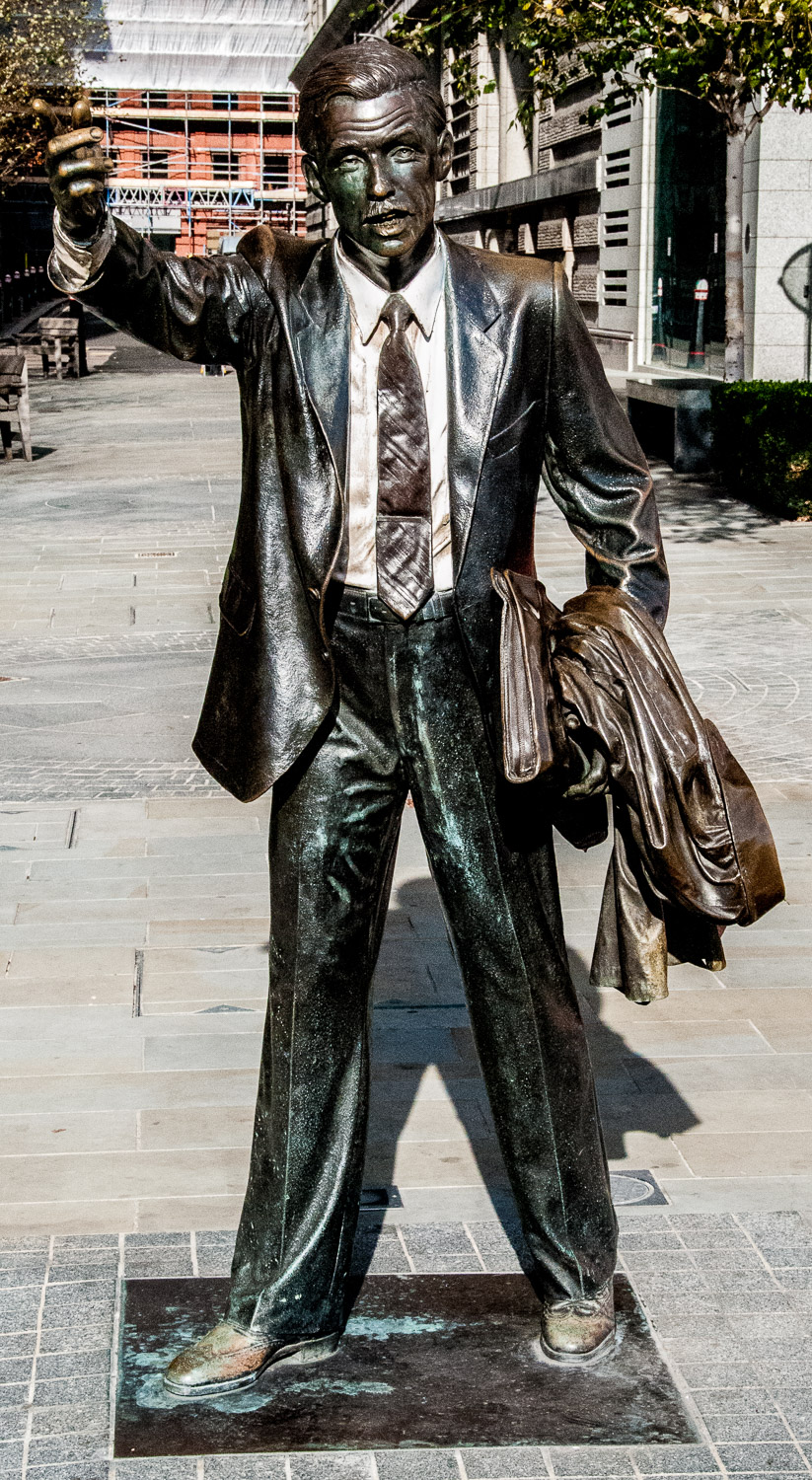

What could be more fun than this chap frantically hailing a taxi …

Taxi! by the American Sculptor J Seward Johnson is cast bronze and dates from 1983. You can find it on the Embankment at the south end of John Carpenter Street (EC4Y 0JP).

It is difficult to grasp nowadays just how much Medieval London was dominated by the Church, but its traces are still very evident today in, for example, the names of streets and surviving districts. Before the Dissolution under Henry VIII more than thirty monasteries, convents, priories and hospitals squeezed into the City’s ‘square mile’ or huddled outside against the still-surviving Roman wall.

This statue of a friar writing in a book with a quill pen is a reminder that the house of the Augustinian Friars stood in what is now Austin Friars (EC2N 2HA) …

Sculptor: T Metcalfe (1989).

These two beautifully carved characters recall the presence here of the Friars of the Holy Cross, also known as the Crutched Friars, after which this street is named (EC3N 2AE) …

Sculptor: Michael Black Architects: Chapman Taylor Partners (1984-85).

The materials are Swedish red granite with heads, hands and feet in off-white Bardiglio marble. They stand on steps, the friar holding the staff and bag representing the active life with his companion holding a scroll representing the contemplative life. Both staff and scroll are made of bronze.

And finally to this great architect, his statue in a niche on the wall of the Bank of England facing Lothbury (EC2R 7HG) …

Sir John Soane Sculptor: William Reid Dick (1930-37).

Sir John wears a long cloak and holds in his left hand a roll of drawings and a set square with the back of the niche discretely decorated with the motifs he habitually used in his buildings. He built his reputation on the work he did as architect of the Bank from 1788 to 1833. Much was lost in later reconstruction, but you can get an idea of what his work was like if you visit the fascinating Bank of England Museum (I have written about it here).

The house where Sir John once lived in Lincoln’s Inn Fields is now a museum and I tell visitors to London it’s a must-see experience. Click here to view the website.