From where I live I have a nice view of my local church, St Giles Without Cripplegate. This image gives a good impression of where this wonderful old church is located within the strikingly modern Barbican Estate …

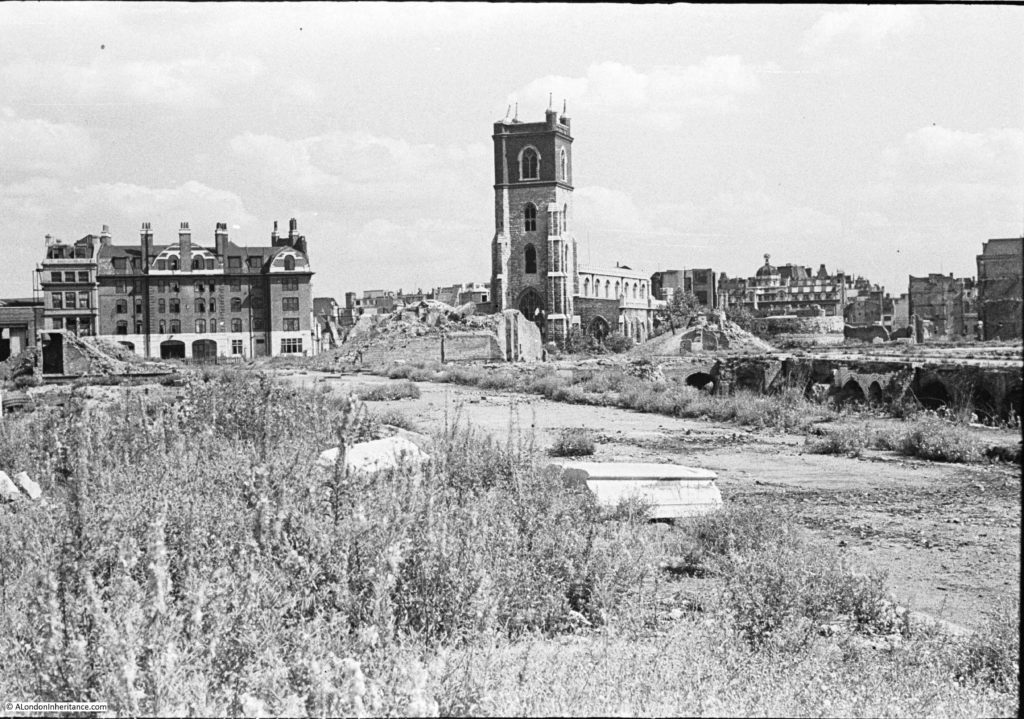

I am always pleased to come across old images of the area, particularly those taken in the three decades after the Second World War. I am indebted to the author of the splendid London Inheritance blog for this view from 1947 showing the devastated landscape …

The building on the left is the Red Cross Street Fire Station.

Another image showing nearby destruction …

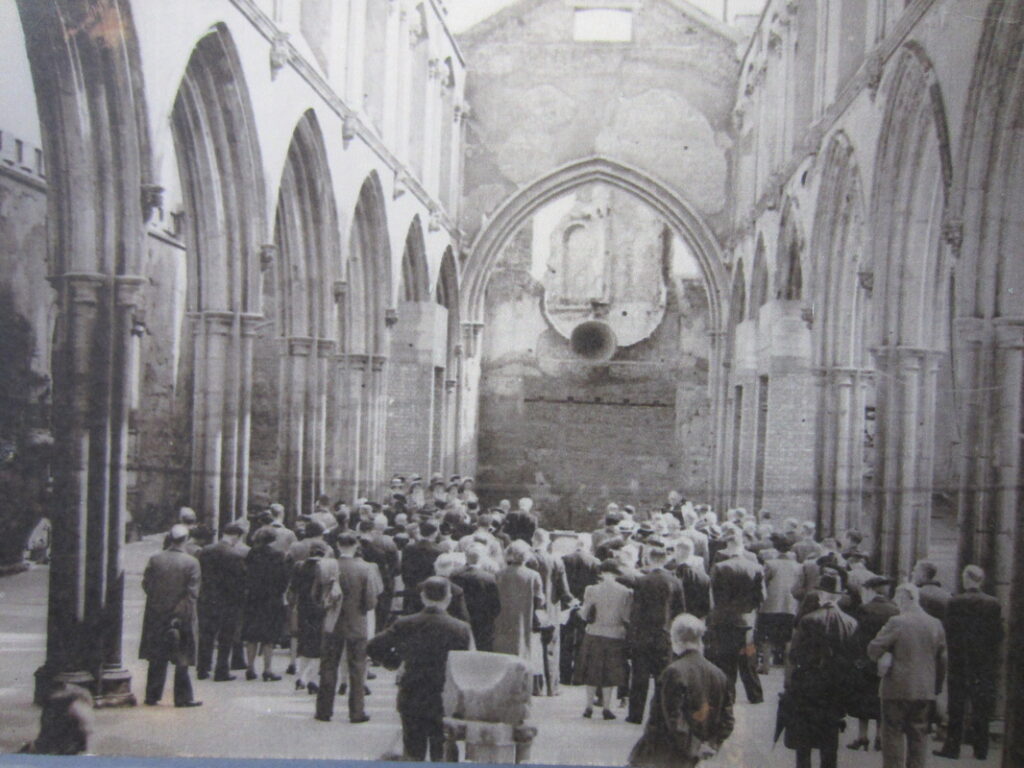

The following photo taken in the days following the raid on the 29th December 1940 shows the damage to the interior of the church …

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: m0017971cl

Since the walls and tower survived a service was possible with the parishioners able to look straight up to the sky …

The inside of the church today. I was fortunate enough to visit when a lady (on the left in the picture) was practising beautifully on the organ …

Here’s an aerial view from the 1960s and the church now has a roof. The more modern looking building on the right is Roman House which has recently been converted into apartments …

In this 21st century aerial image you can just make out the church’s green roof …

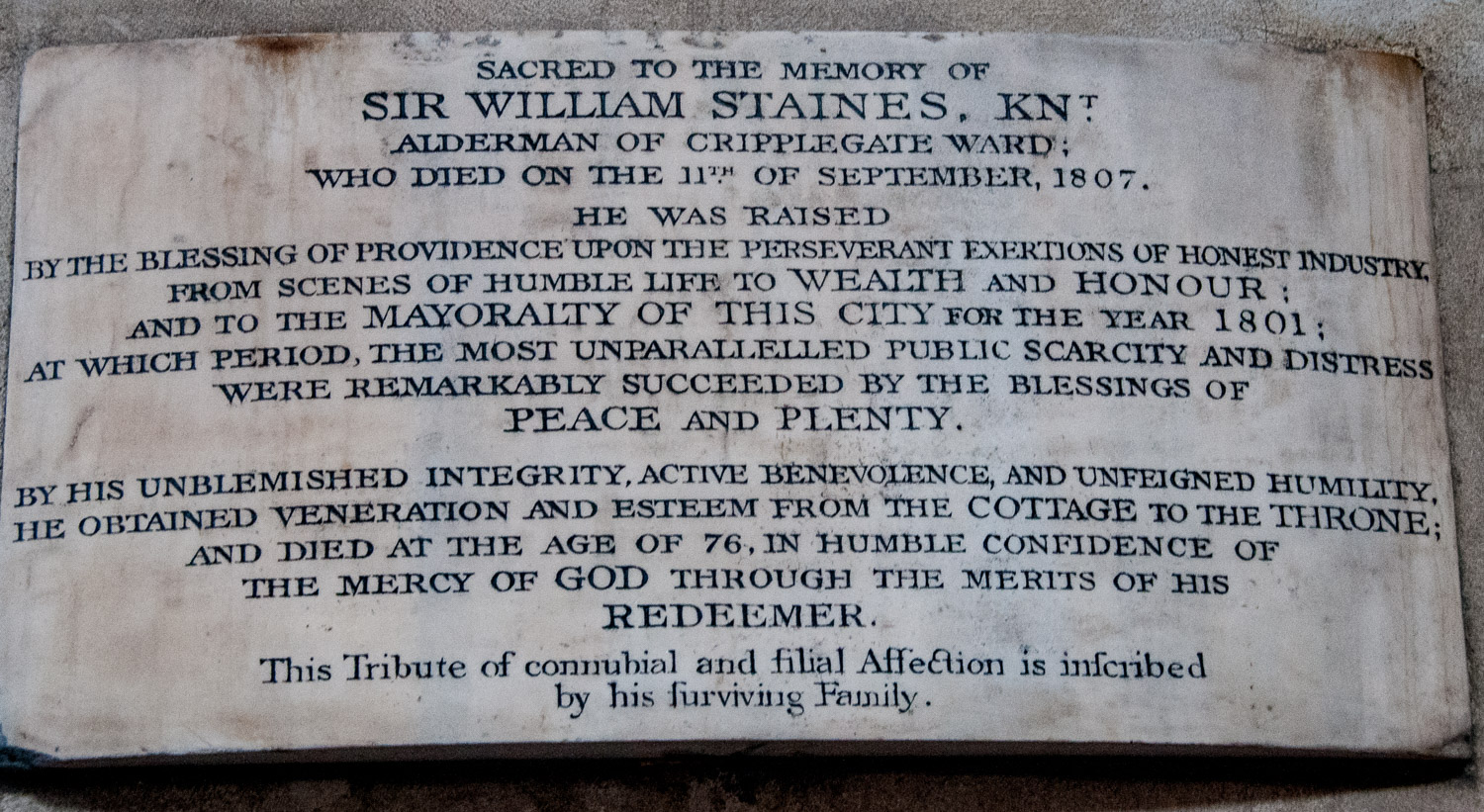

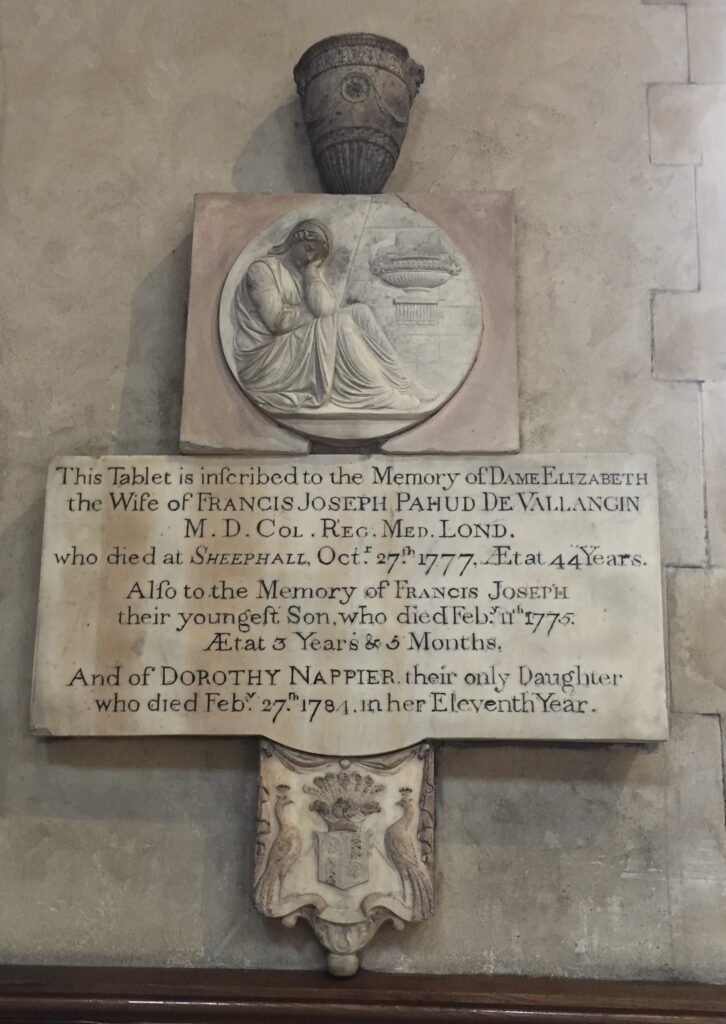

Some monuments remain from the old pre-Blitz building.

There is this touching memorial to a favourite character of mine, Sir William Staines …

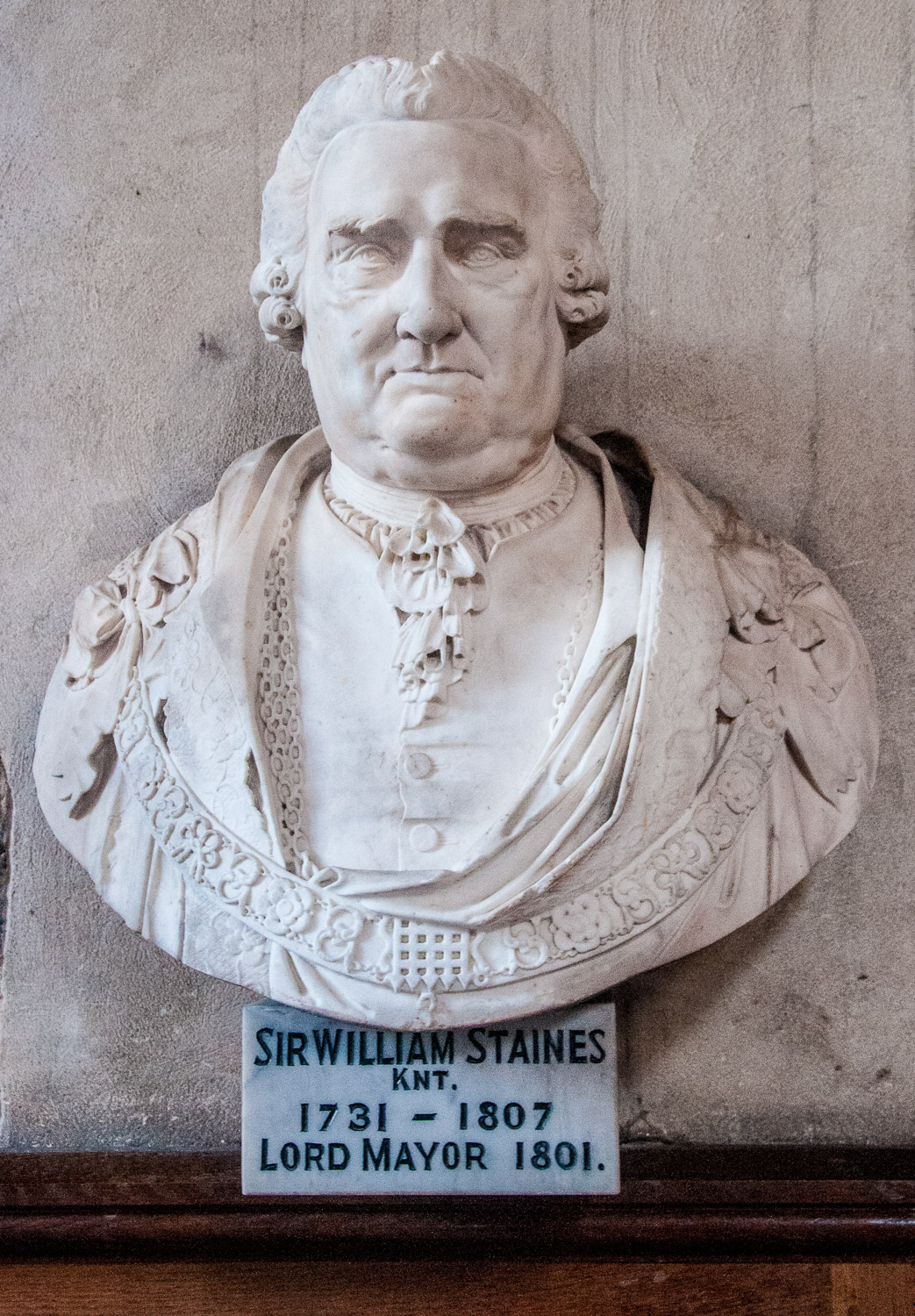

And here is the man himself …

Staines had extremely humble beginnings working as a bricklayer’s labourer, but eventually accumulated a large fortune which he generously used for philanthropic purposes. He seemed to recall his own earlier penury when he ensured that the houses he built for ‘aged and indigent’ folk would have ‘nothing to distinguish them from the other dwelling-houses … to denote the poverty of the inhabitant’.

British History Online records an encounter he had with the notorious John Wilkes who referred rather rudely to Staines’ original occupation …

The alderman was an illiterate man, and was a sort of butt amongst his brethren. At one of the Old Bailey dinners, after a sumptuous repast of turtle and venison, Sir William was eating a great quantity of butter with his cheese. “Why, brother,” said Wilkes, “you lay it on with a trowel!”

Incidentally, Wilkes is also commemorated in the the City in Fetter Lane where a striking statue of him honestly portrays his famous squint …

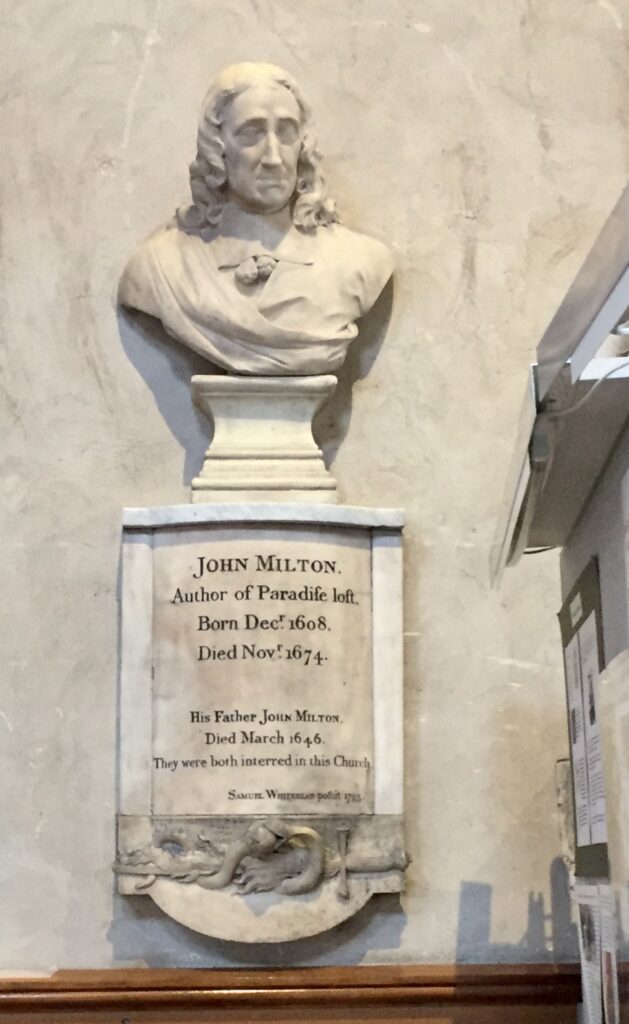

John Milton (1608-1674), the poet and republican, is perhaps the most famous former parishioner of St Giles and his statue stands by the south wall of the church …

It’s made of metal, which means it is one of the few memorials in the church that survived the bombing in the Second World War. It is the work of the sculptor Horace Montford (c1840-1919) and is based on a bust made in about 1654.

He used to be outside and was blasted off his plinth during the bombing …

There is also this commemorative plaque …

And a bust which clearly indicates his later-life blindness …

Milton was buried in the church next to his father, however he was not allowed to rest in peace.

British History Online reports the shocking event as follows …

‘A sacrilegious desecration of his remains, we regret to record, took place in 1790 … The disinterment had been agreed upon after a merry meeting at the house of Mr. Fountain, overseer, in Beech Lane, the night before, Mr. Cole, another overseer, and the journeyman of Mr. Ascough, the parish clerk, who was a coffin-maker, assisting’.

Having identified where they thought Milton’s grave was, they dug down almost six feet, found a coffin, and removed the lid. The report goes on …

‘Upon first view of the body, it appeared perfect, and completely enveloped in the shroud, which was of many folds, the ribs standing up regularly. When they disturbed the shroud the ribs fell. Mr. Fountain confessed that he pulled hard at the teeth, which resisted, until some one hit them a knock with a stone, when they easily came out. There were but five in the upper jaw, which were all perfectly sound and white, and all taken by Mr. Fountain. He gave one of them to Mr. Laming. Mr. Laming also took one from the lower jaw; and Mr. Taylor took two from it. Mr. Laming said that he had at one time a mind to bring away the whole under-jaw with the teeth in it; he had it in his hand, but tossed it back again’.

As if that wasn’t undignified enough,’Elizabeth Grant, the gravedigger … now took possession of the coffin; and, as its situation under the common councilmen’s pew would not admit of its being seen without the help of a candle, she kept a tinder-box in the excavation, and, when any persons came, struck a light, and conducted them under the pew; where, by reversing the part of the lid which had been cut, she exhibited the body, at first for sixpence and afterwards for threepence and twopence each person’.

The body was reburied but rumours spread that it wasn’t Milton in the coffin, but a woman. So Milton was dug up a second time and the surgeon in attendance examined the bones — what were left of them — and pronounced them to be masculine. Only then was Milton, at last, allowed to rest only to be permanently obliterated in the bombing.

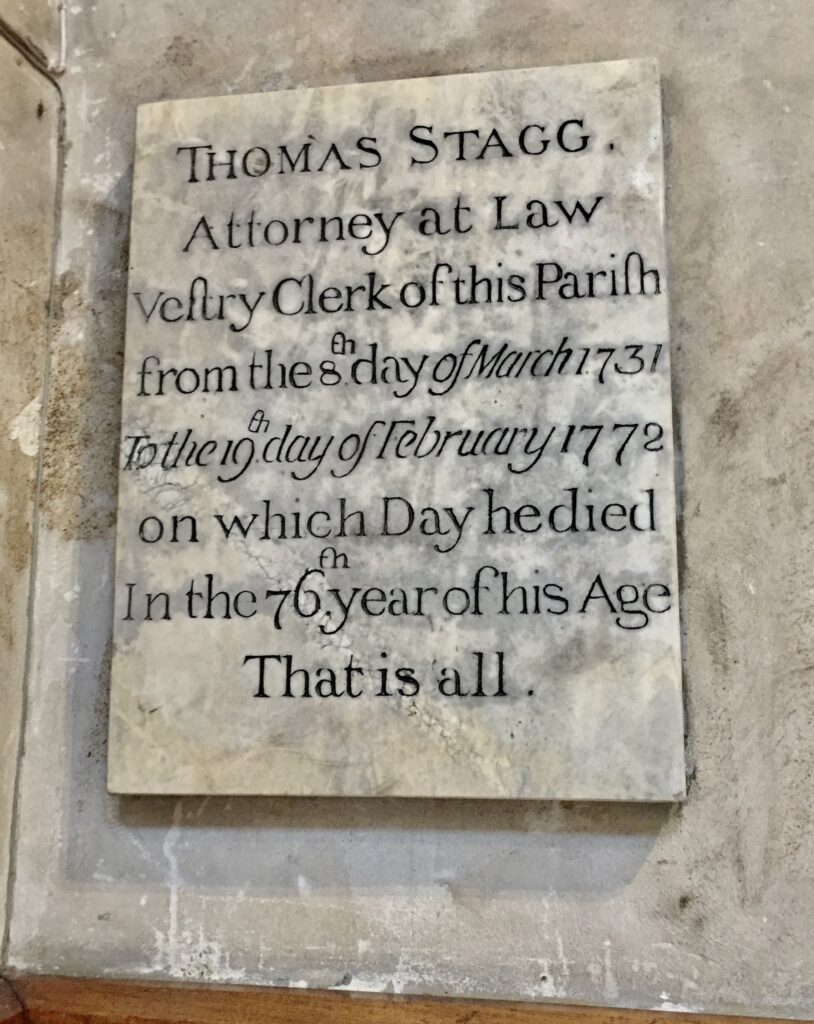

Notwithstanding the generous memorials to the great and the good, I was captivated by this modest plaque on the south wall …

An attorney at law who obviously believed in brevity. No Latin exhortation of his virtues, no figures of a grieving widow and children, only the important facts and the bald, concluding statement ‘That is all’.

There is a lot more to see at St Giles such as modern stained glass …

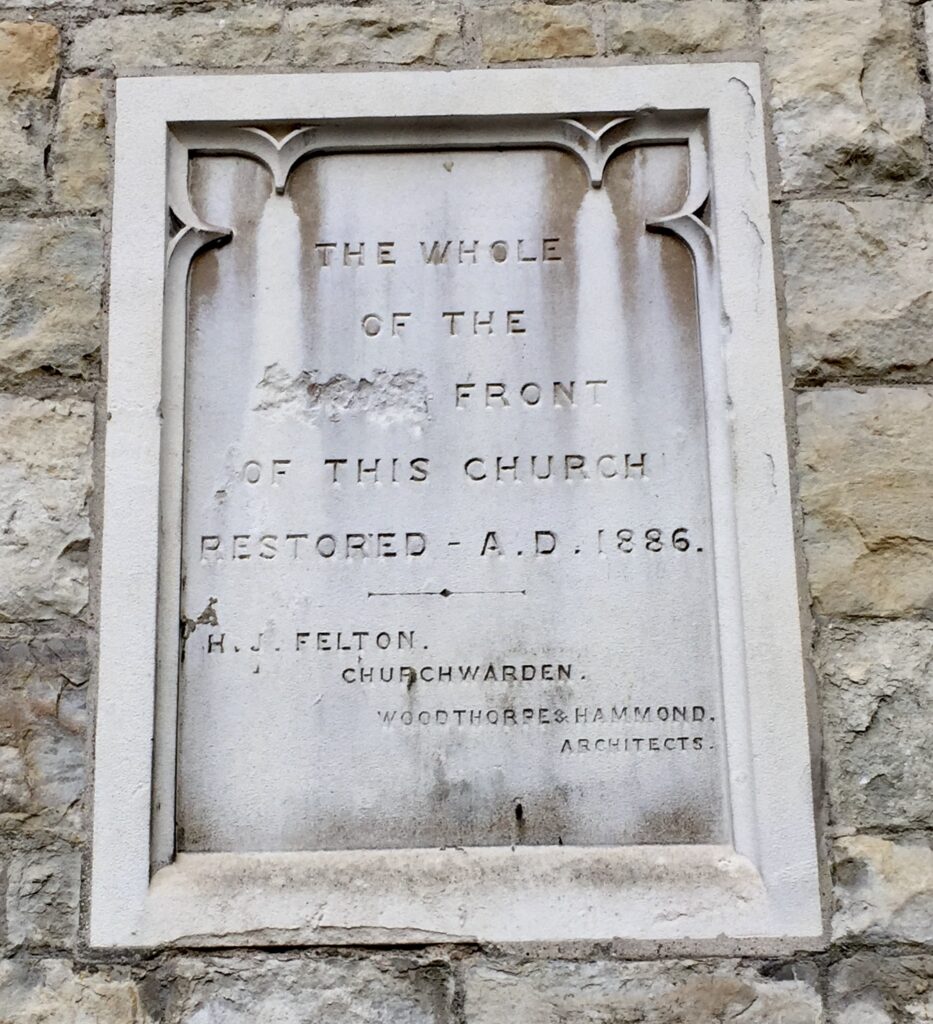

And intriguing inscriptions, both inside …

And outside …

But for the moment ‘that is all!’

If you would like to follow me on Instagram here is the link …